Mapamundi hecho por Johannes Kepler.

Planisferio actual de la Tierra creado por composición de fotografías de satélite

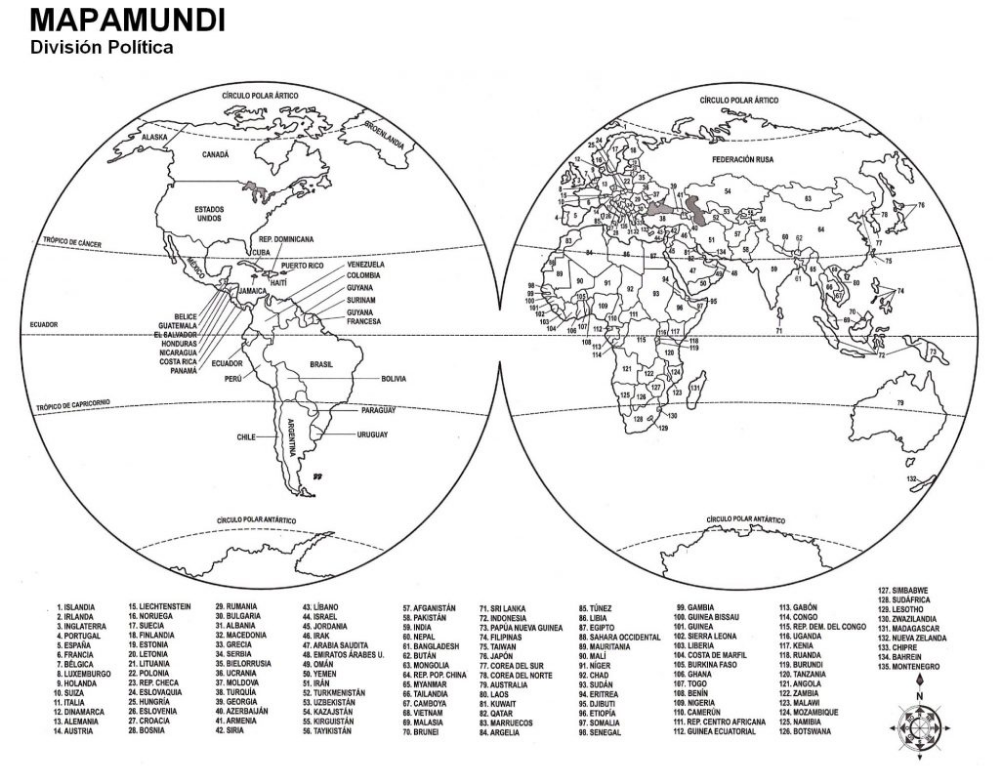

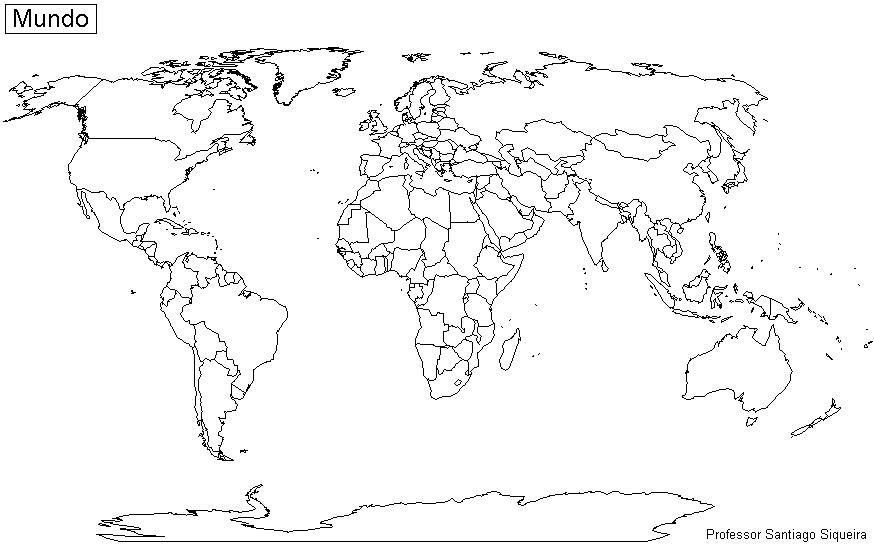

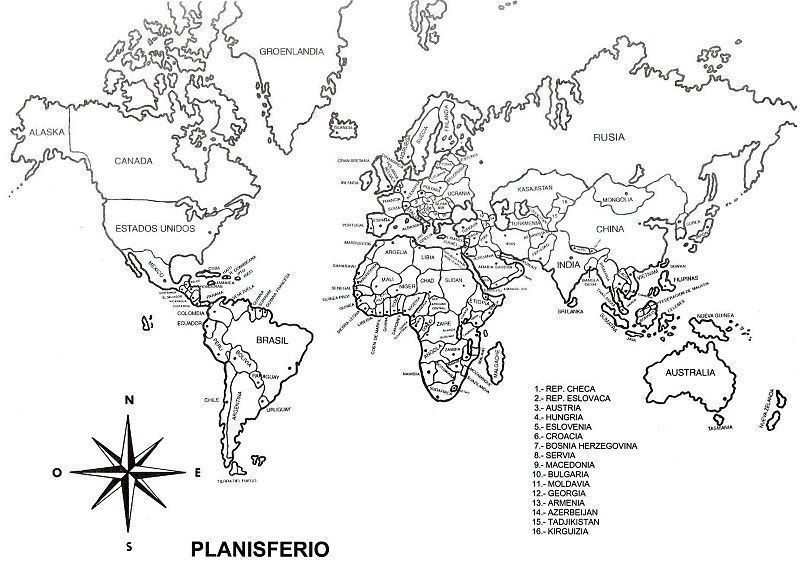

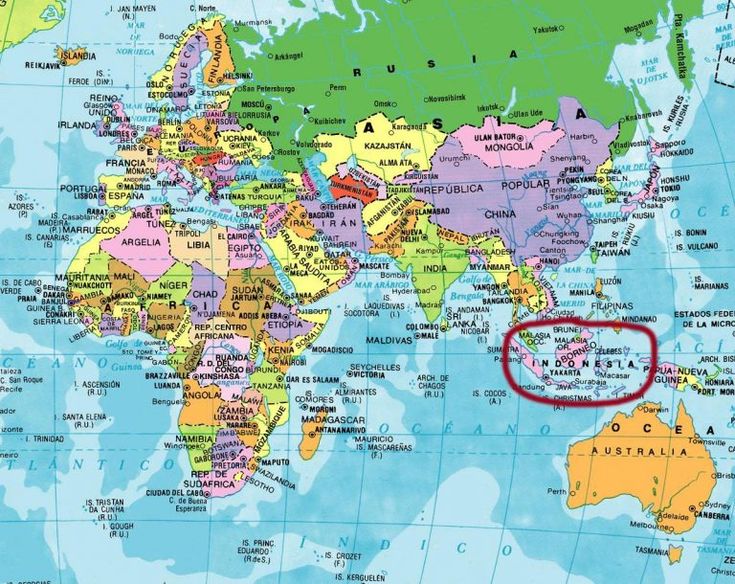

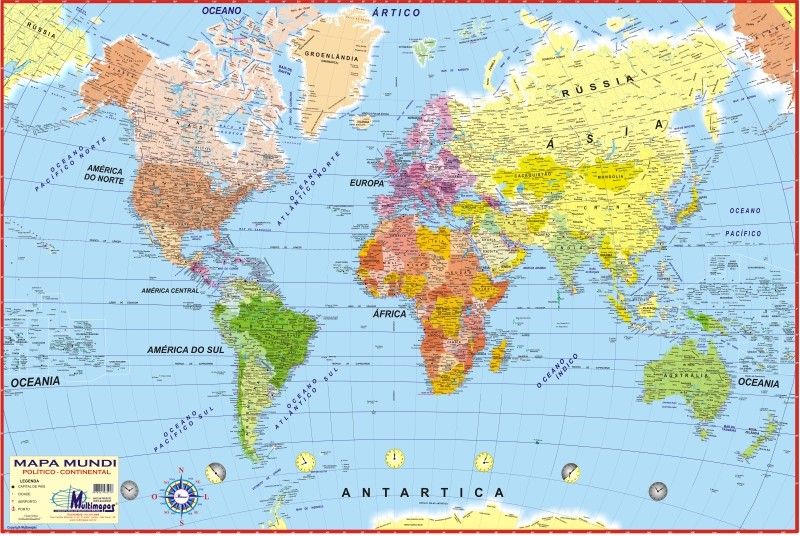

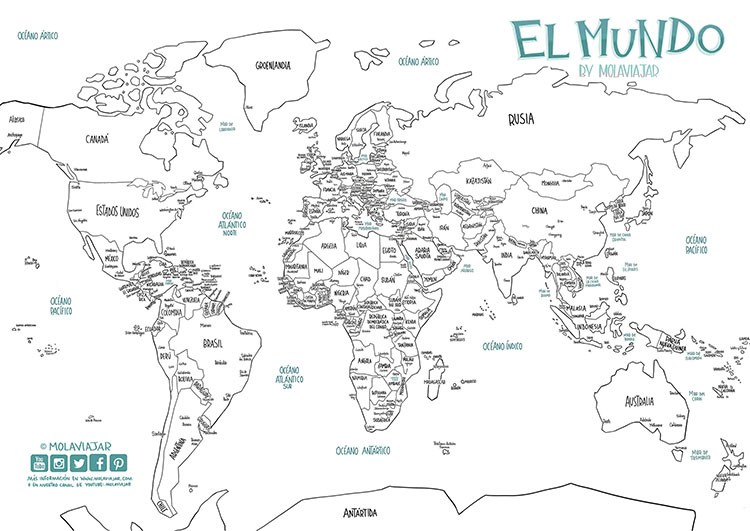

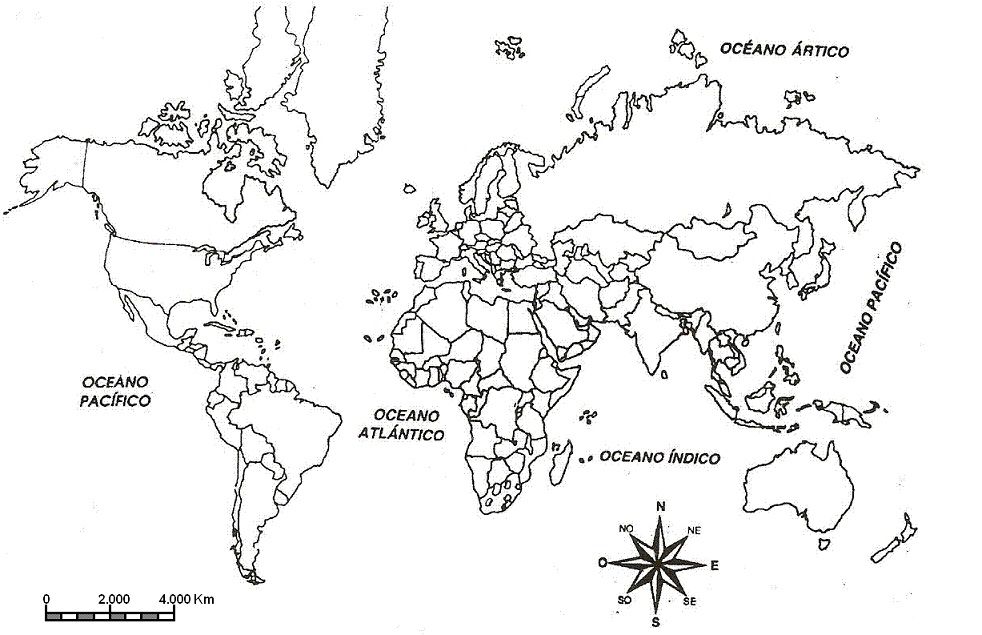

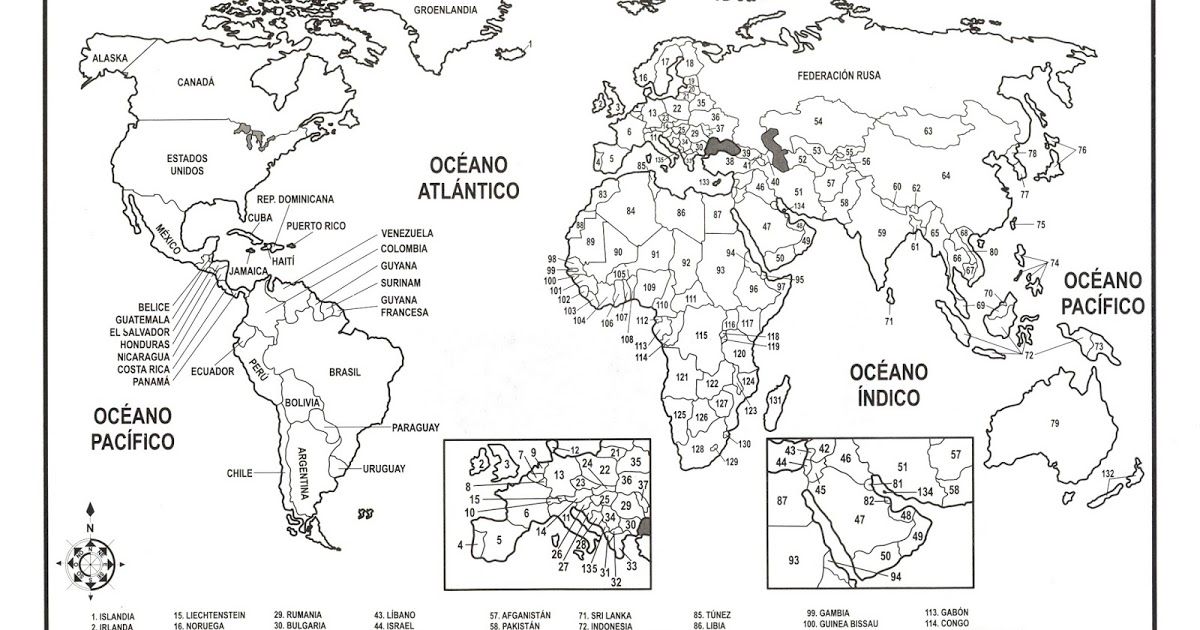

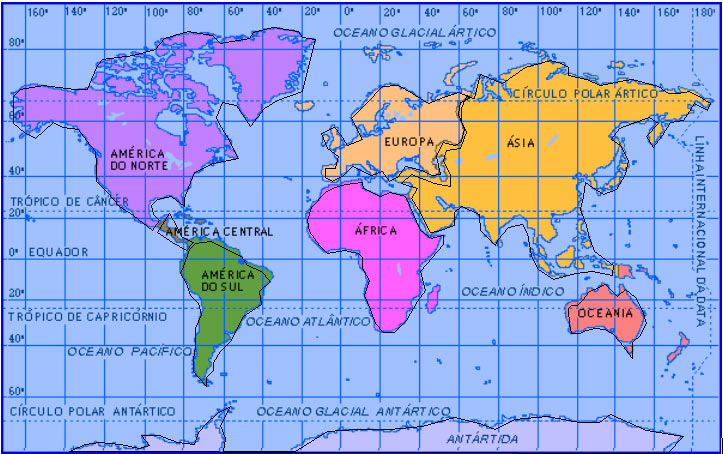

Un mapamundi (del latín medieval mappa mundi, «mapa del mundo»[1]) es una representación cartográfica (mapa) de toda la superficie terrestre. El material sobre el que se representa suele ser de papel y en un principio era de piel.

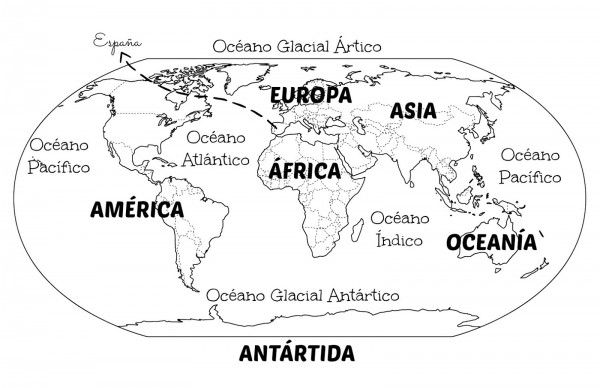

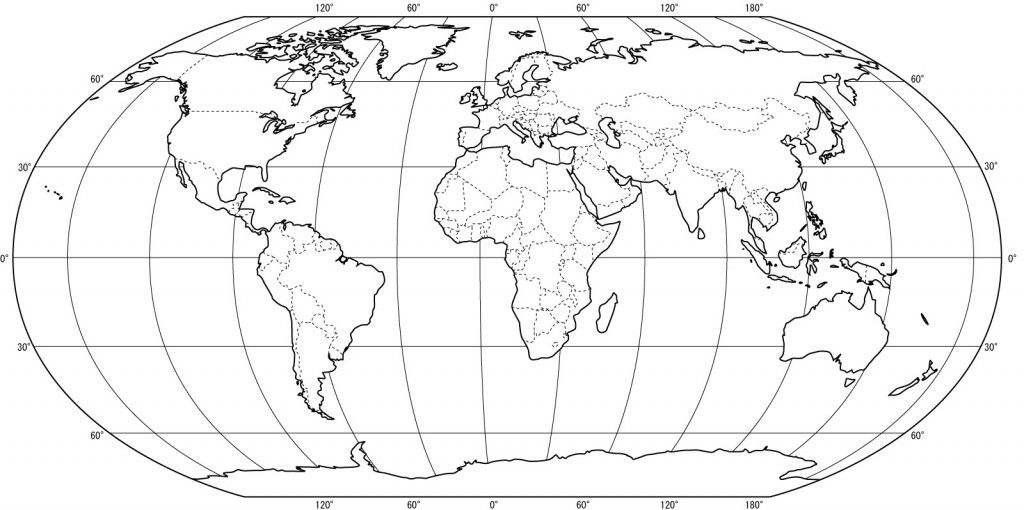

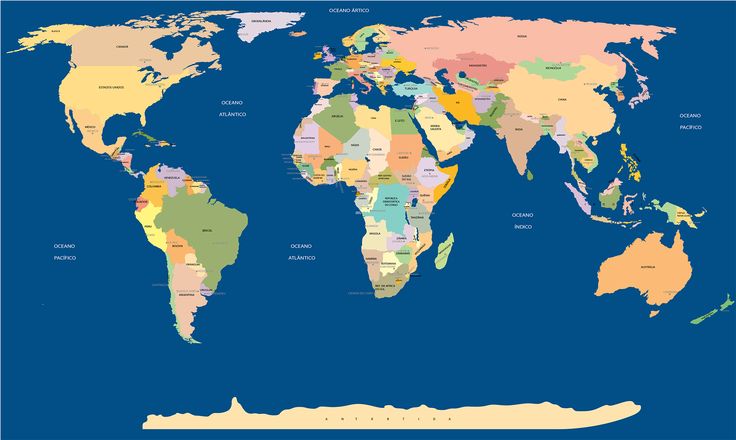

Dependiendo de su forma, un mapamundi puede ser un globo terráqueo, que reproduce a escala la forma prácticamente esférica del geoide; o un planisferio terrestre, que reproduce a escala el resultado teórico de algún tipo de proyección geográfica de la esfera terrestre en un plano. Existen planisferios celestes para la representación de las estrellas.[1]

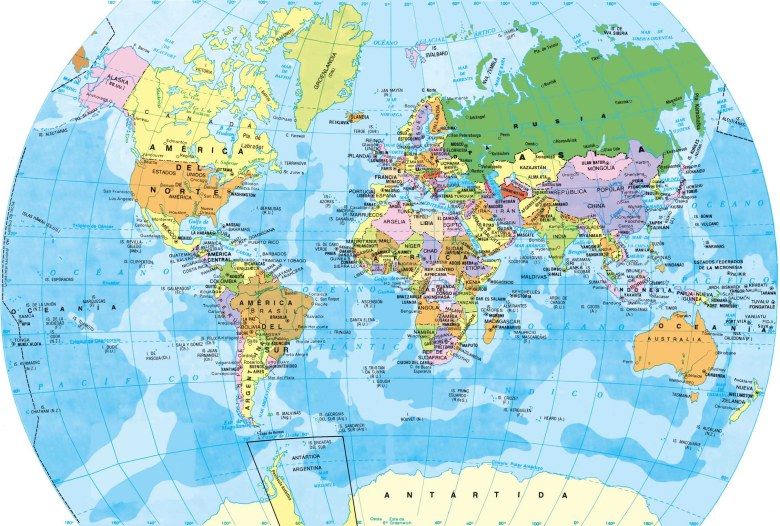

Los mapamundis suelen presentarse en forma de distintos tipos de mapa temático dependiendo del detalle permitido por la escala, que cuando es muy alta, se limita a mapas parciales y no a mapamundis.

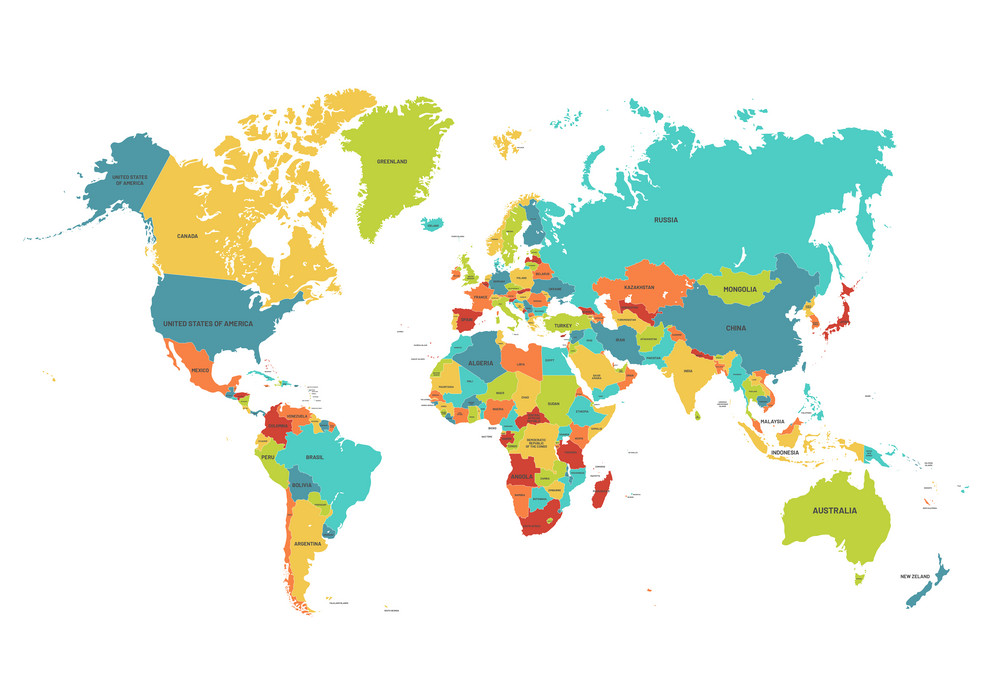

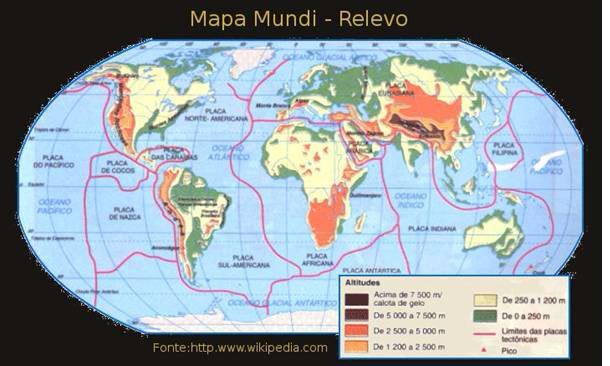

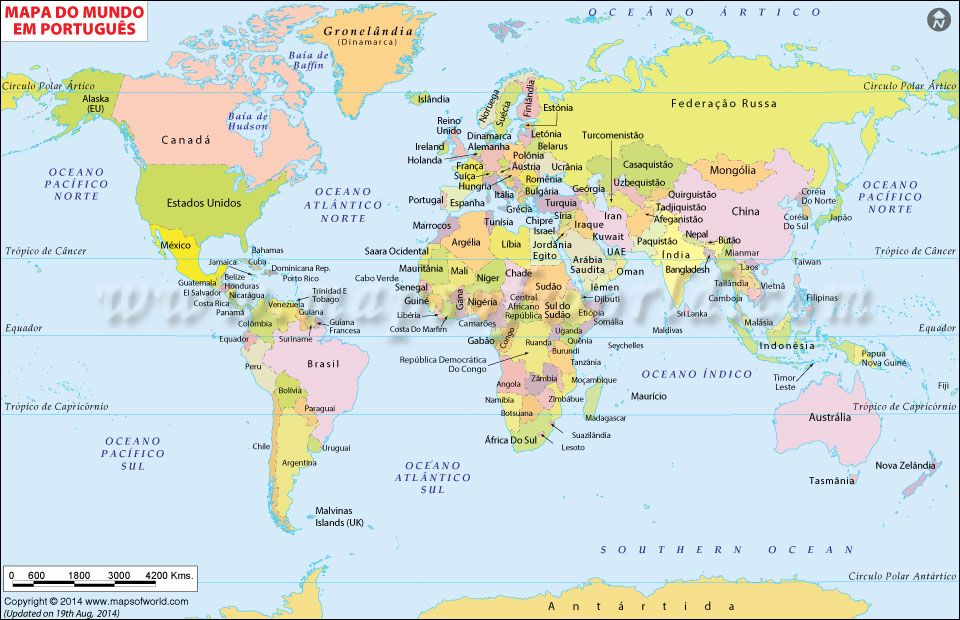

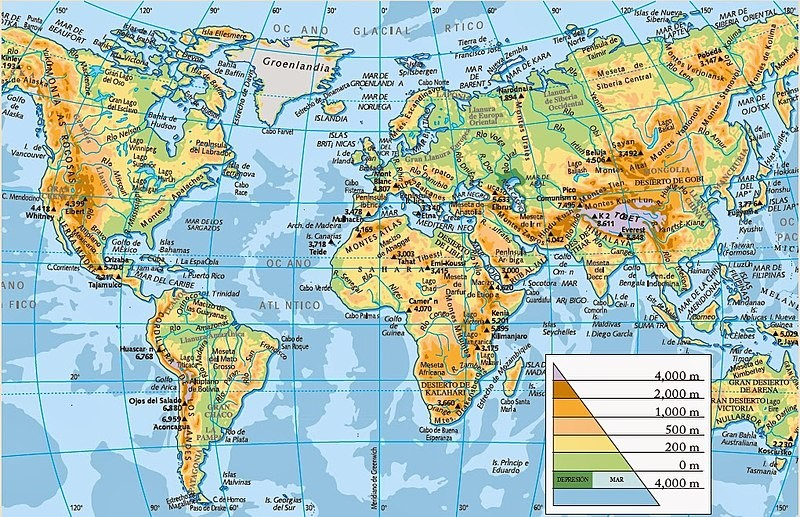

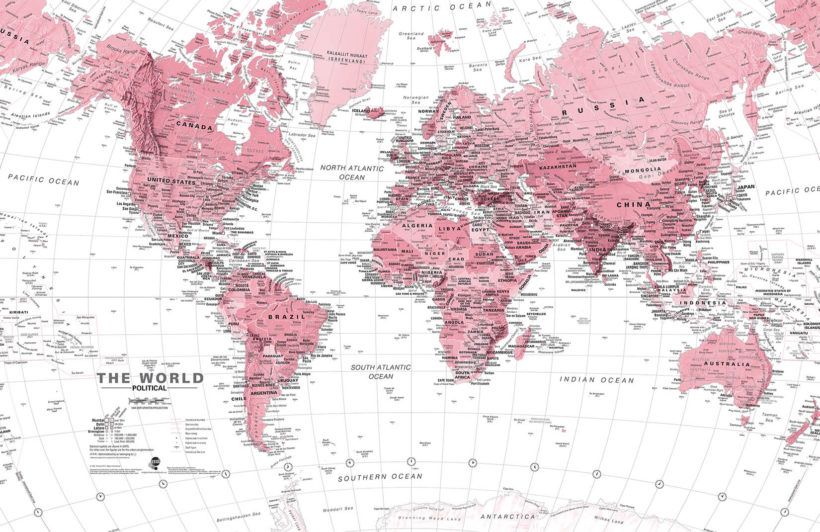

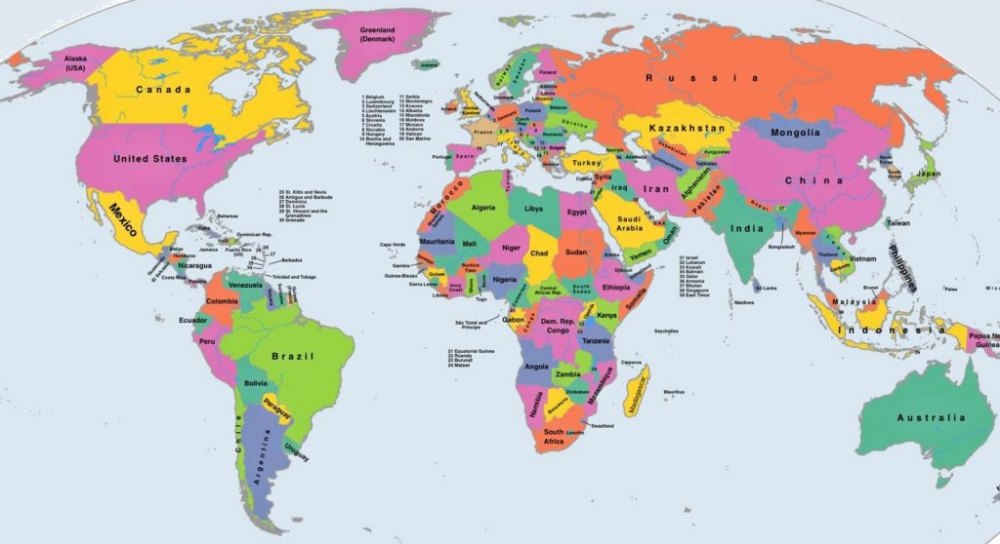

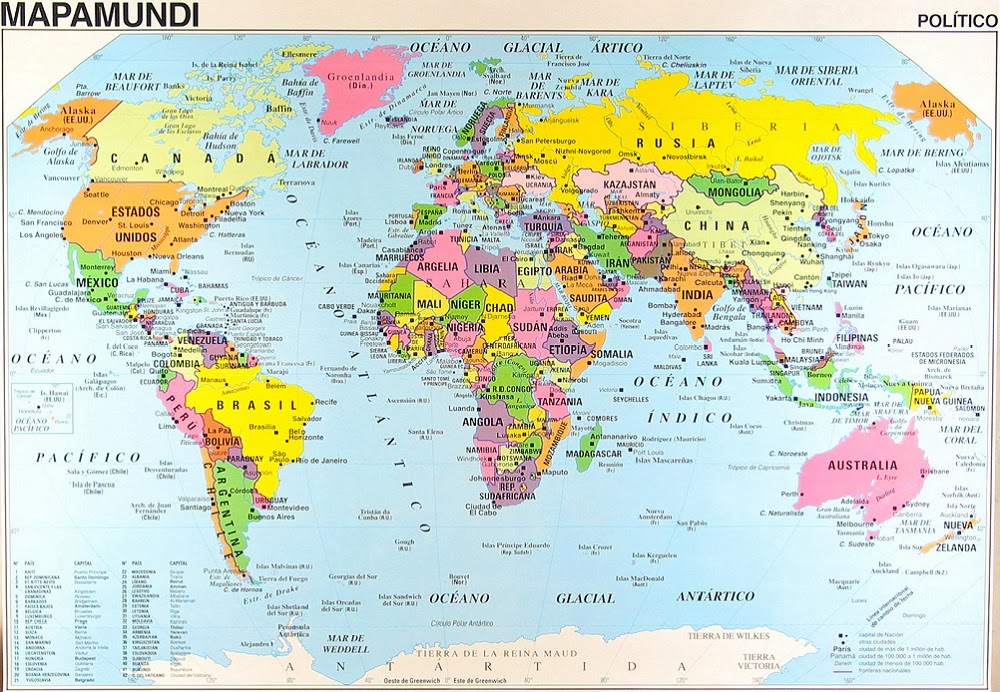

El propósito más importante de un mapa político es mostrar las fronteras territoriales. El propósito de un mapa físico es mostrar las características físicas o accidentes geográficos (como montañas, ríos, lagos, mares, líneas de costa de islas y continentes o tipos de paisaje específicos -cordilleras, desiertos, selvas, marismas, manglares, glaciares, banquisas, etcétera-).

Otros usos suelen restringirse a mapas parciales, aunque pueden reflejarse en un mapamundi si se prescinde de los detalles, y se limita su reflejo un nivel muy general: Los mapas geológicos muestran las características de las rocas, líneas de fallas, y estructuras superficiales. Los mapas topográficos representan las curvas de nivel, identificando distintos accidentes físicos o usos del suelo con símbolos convencionales apropiados (los símbolos cartográficos: por ejemplo, los vértices geodésicos con un triángulo, los cultivos con iconos significativos, las carreteras con líneas rojas de distintas dimensiones, los ferrocarriles con líneas negras, las fronteras con líneas continuas o discontinuas, las ciudades con círculos de tamaño proporcional a su importancia, o con su trazado aproximado -en caso de mapas muy detallados-, llegando al detalle de reflejar casas e instalaciones humanas de todo tipo).

El mapa del mundo descrito por Posidonio entre el 150 y el 160 a. C.

El mapa de Juan de la Cosa (dibujado en El Puerto de Santa María, 1500) es la representación oficial más antigua de tierras americanas.

Se sabe que los mapas aparecieron alrededor del año 2500 a. C. debido al descubrimiento de unas tablillas de barro de origen babilónico, y que representaban los valles del río Éufrates. Al comienzo se representaban los lugares cercanos y familiares y es de suponer que poco a poco se iría incorporando más y más territorio hasta que finalmente se representara toda la superficie terrestre. Los primeros en tener una consciencia global fueron los babilonios que pensaban en la tierra como un plato plano de tierra con un gran río que dividía en dos partes; griegos como Tales de Mileto ya sugerían la esfericidad de la tierra en los siglos VI y V antes de Cristo.

Los discípulos de Thales, Estrabón y finalmente fue Anaximandro de Mileto el primero en empezar a cartografiar el mundo globalmente: con los ríos y los mares. En este momento apareció el concepto ecúmene en el que el mundo habitado era dos veces más grande en eje este-oeste que en norte-sur, evidentemente este mundo centraba su existencia en el mediterráneo.

En el año 330 a. C. Piteas establece un periplo en el que llega a visitar diversos países del norte, entre ellos la isla de Thule, que se ha identificado tanto con Islandia como la península escandinava, que podría haber interpretado como una isla.[2]

Véase también: Mapamundi de Ptolomeo

El trabajo de Ptolomeo se fundamenta en el de otro cartógrafo anterior denominado Marinus de Tiro. Ptolomeo trabaja en su Geographía mostrando ya conceptos globales de la cartografía, así como un estudio teórico profundo sobre el tema.

Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa en su obra Historia de los Incas indica que esta cultura ya disponía de mapas mundi en el siglo V y los Aztecas a la llegada de Hernán Cortés ya disponían de divisiones administrativas-catastrales sobre los territorios bajo su jurisdicción, de hecho este descubrimiento le sirvió para la conquista de Honduras.

La Edad Media produjo en Europa diversos mapamundis, todos ellos con diferentes denominaciones como: “discario”, “Orbis Terrarum”, o, por utilizar la expresión más general, “mapa de T en O”. El nombre de estos mapamundis deriva de Isidoro de Sevilla, que en sus Etimologías representa un mundo circular plano (representado evidentemente por la O) dividido por tres partes iguales de masas de Agua (La T). El trazo vertical de la T corresponde al Mediterráneo y el trazo horizontal de la T a diversos ríos y mares. Esta disposición fue muy repetida y dio lugar a esta denominación.

Artículo principal: Proyección geográfica

Los mapas que representan la superficie de la Tierra usan una proyección, una manera de traducir la superficie real tridimensional de un geoide a un dibujo bidimensional.

La proyección más conocida de un mapamundi es la Proyección de Mercator, una proyección cilíndrica originalmente diseñada como forma de carta de navegación y que tiene como principal virtud reflejar con exactitud los ángulos en que un rumbo corta la red de meridianos y paralelos, haciendo muy sencilla la tarea del navegante sobre el mapa. Sin embargo, al representar del mismo tamaño todos los paralelos, hace que las zonas ecuatoriales queden representadas con una superficie inferior, en comparación, a las zonas templadas (tanto las del hemisferio norte como las del hemisferio sur), mientras que las zonas cercanas a ambos polos aparecen representadas con una superficie muy superior.

Desde una perspectiva tercermundista se crítica esa forma de representación como invisibilizadora y eurocéntrica (dado que la mayor parte de los países subdesarrollados están en las zonas cercanas al ecuador y la mayor parte de los desarrollados en las zonas templadas), y se proponen alternativas, como la proyección de Peters, que representa proporcionalmente las superficies, aunque deforma los perfiles de los países y continentes y los ángulos de la red de coordenadas.

También se propone invertir los puntos cardinales, para que el sur aparezca arriba y el norte abajo, dado que esas posiciones son totalmente convencionales y no significan que exista algún tipo de prioridad real en la disposición de los hemisferios ni algún punto de referencia más válido que otro.

Las propuestas de imponer la difusión del mapa de Peters o del mapa invertido en los medios de comunicación y en la educación como forma de cambiar las mentalidades reciben a su vez acusaciones de ser una forma de corrección política.

Existen muchas otras formas de proyección, unas limitadas a una parte del geoide (con ventajas en cuanto a la precisión en representar superficies y formas, pero que no pueden dar origen a un planisferio) y otras extensibles a una representación total con distintos tipos de deformación. La representación de bandas meridianas en forma de huso, que recuerda la forma en que se cortan las sandías (o también puede pelarse una naranja), tiene la ventaja de representar fielmente tanto la forma como la superficie, pero no la distancia entre unos puntos y otros, al dejar espacios vacíos.

Una proyección que tiene menor distorsión del tamaño relativo de las regiones es el mapa Dymaxion que además tiene menos distorsión de formas y no tiene dirección que vaya arriba.

Proyección de Mercator.

Proyección de Peters.

Proyección transversa de Mercator con bandas meridianas de 20 grados.

Proyección de Aitoff.

Proyección de Robinson.

Proyección de Robinson centrada en el océano Pacífico, comúnmente utilizada en China y Japón.

Mapa Dymaxion o proyección de Fuller.

Proyección cartográfica de bajo error Winkel tripel adoptada por National Geographic Society como mapa de referencia

ª edición). Consultado el 25 de febrero de 2019.

ª edición). Consultado el 25 de febrero de 2019.

| Control de autoridades |

|

|---|

Te explicamos qué es el mapamundi, su historia y qué formas puede tomar. Además, qué son las proyecciones, los paralelos y los meridianos.

El mapamundi puede servir de base para la elaboración de otros mapas.

El mapamundi (palabra heredada del latín medieval mappa mundi, o sea, “mapa del mundo”) es una representación cartográfica de la totalidad de la superficie terrestre, es decir, se trata de un mapa del mundo entero.

Dependiendo de su forma, un mapamundi puede llamarse de dos modos:

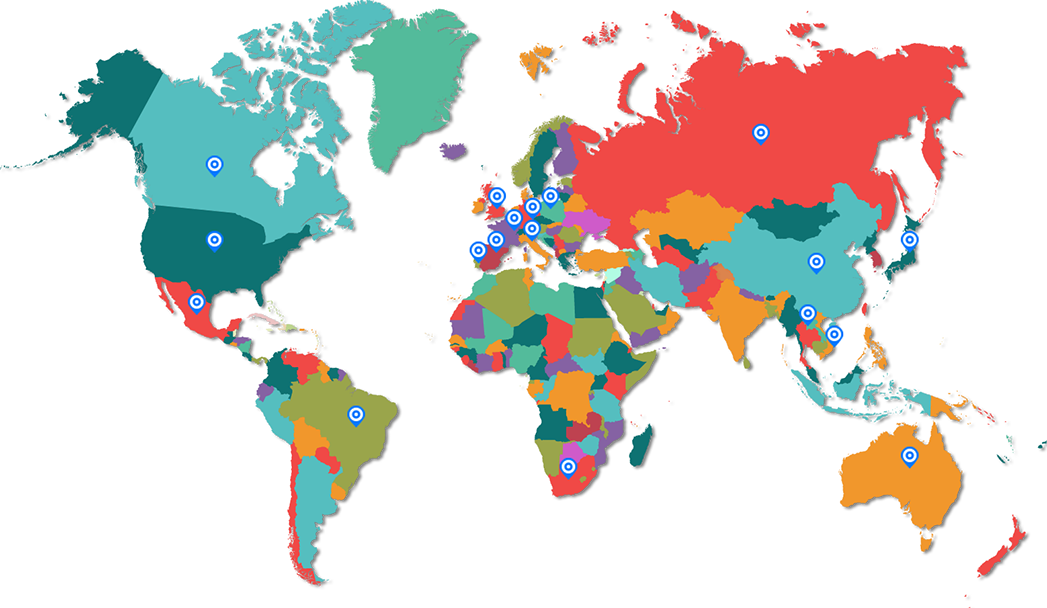

Los mapamundis son una herramienta muy antigua, que se elabora con el propósito de servir de guiatura en asuntos de geografía y de política, pudiendo servir de base para la elaboración de otros mapas, como el mapa político (que muestra las divisiones de los países), el mapa físico (que muestra los accidentes geográficos) y el mapa topográfico (que muestra las curvas de nivel del relieve), entre muchos otros usos especializados.

En los mapamundis no solo aparece la representación de la superficie terrestre (los continentes, islas y los océanos), sino también los símbolos y signos de uso geográfico para organizar, sectorizar y estructurar imaginariamente al planeta. Así, suelen trazarse también las líneas fronterizas, los ríos y las líneas de altura, además de los paralelos y meridianos, el ecuador, etcétera. También es normal destacar la ubicación de las ciudades y capitales, así como otros elementos que puedan resultar de interés particular.

Así, suelen trazarse también las líneas fronterizas, los ríos y las líneas de altura, además de los paralelos y meridianos, el ecuador, etcétera. También es normal destacar la ubicación de las ciudades y capitales, así como otros elementos que puedan resultar de interés particular.

Ver también: Cartografía

La exploración de Asia y África incorporó nuevos retos a la hora de imaginar el mundo.

Desde épocas muy tempranas la humanidad conoció la utilidad y la valía de los mapas, y muchas de las civilizaciones antiguas quisieron trazar mapas lo más exactos y exhaustivos del mundo que conocían. Los primeros intentos hallados de mapamundi datan de alrededor del 2500 a. C., y consisten en trazos en tablillas de barro babilónicas, pero se limitaban a la representación del valle del río Éufrates.

Los antiguos griegos, por su parte, sabían de la esfericidad de la Tierra y quisieron trazar algún tipo de mapa total. A esta tarea se abocó particularmente el principal pupilo de Thales de Mileto, el geógrafo y filósofo Anaximandro de Mileto (c. 610-546 a. C.), creador del primer mapa del mundo conocido, cuya apariencia se desconoce pero en el que estaban representados el mar Mediterráneo, el mar Negro, los ríos Éufrates y Phasis, y tres grandes continentes: Europa, Asia y Libia, rodeados de un cinturón de agua llamado Océano.

610-546 a. C.), creador del primer mapa del mundo conocido, cuya apariencia se desconoce pero en el que estaban representados el mar Mediterráneo, el mar Negro, los ríos Éufrates y Phasis, y tres grandes continentes: Europa, Asia y Libia, rodeados de un cinturón de agua llamado Océano.

Este primer mapamundi serviría de base para una versión mucho más avanzada, creada por el geógrafo y astrónomo griego Claudio Ptolomeo (c. 100-170 d. C.), en la que no solo representó numerosos ríos de los tres continentes conocidos por Anaximandro, sino que incorporó por primera vez líneas imaginarias longitudinales y latitudinales.

El mapamundi de Ptolomeo posiblemente formó parte de su obra Geografia, escrita alrededor del 150 d. C., pero tampoco se conserva hoy en día. Únicamente perduran las reconstrucciones que hicieron más de 1000 años después los monjes bizantinos dirigidos por el gramático y teólogo Maximus Planudes (c. 1260-c. 1305). Sin embargo, la elaboración de mapamundis fue una actividad muy común durante el Medioevo europeo.

La posterior exploración de Asia y de África, así como el descubrimiento de América, incorporó nuevos retos a la hora de imaginar el mundo, que hasta entonces se había reducido al mar Mediterráneo y sus zonas aledañas, siempre dibujado a manera de “T en O”, o sea, en el círculo del mundo se distinguían tres continentes separados por el Mediterráneo, formando una “T” de separación entre ellos. Estos eran mapas poco interesados en la exactitud geográfica, que reflejaban más bien ideas teológicas y políticas.

Se toma como el primer mapamundi “científico” el elaborado por el cartógrafo portugués Diego Ribero en 1527, en el que ya aparecían América y Oceanía, gracias a la información de exploradores como Fernando de Magallanes, Juan Sebastián Elcano y Esteban Gómez. Pero no sería hasta el siglo XVIII en que nuevas técnicas de proyección geográfica permitieron el surgimiento de mapas más similares a los actuales, que gracias a la invención de los aeroplanos y la fotografía en los siglos venideros, adquirieron la exactitud actual.

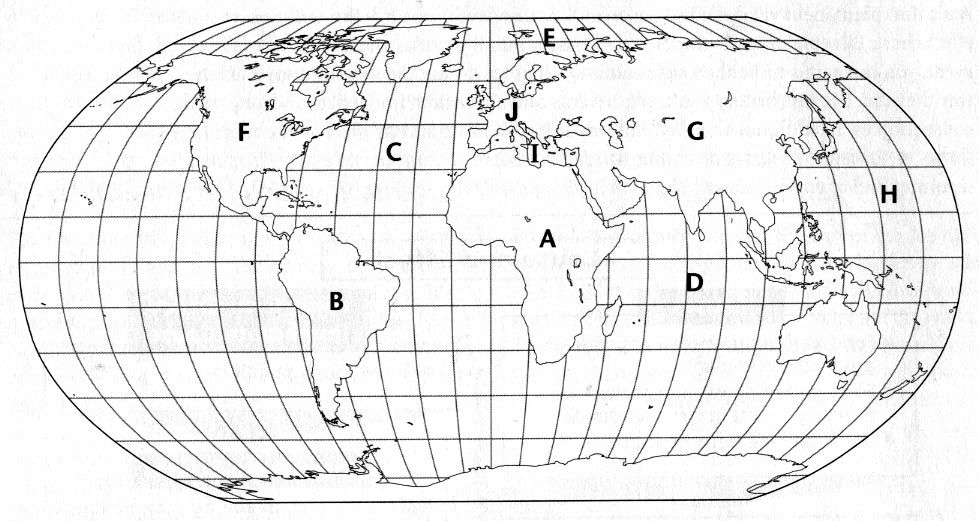

Los mapamundis tienen dos tipos principales de líneas imaginarias, que surcan el mundo longitudinal y latitudinalmente, trazando así una cuadrícula, útil para establecer un sistema mundial de coordenadas geográficas que permite orientarse en cualquier lugar de la superficie terrestre. Estas líneas imaginarias son:

Para esto, se utiliza además un meridiano “cero” de referencia, que pasa por el antiguo observatorio de Greenwich en Londres, Reino Unido. A partir de él, se avanza un grado por meridiano en un sentido positivo (+1) o negativo (-1) dependiendo de si se avanza hacia el este o el oeste respectivamente. Estas líneas sirven para determinar el huso horario.

A partir de él, se avanza un grado por meridiano en un sentido positivo (+1) o negativo (-1) dependiendo de si se avanza hacia el este o el oeste respectivamente. Estas líneas sirven para determinar el huso horario.

Para esto, además, se utiliza al ecuador (la línea imaginaria que divide al mundo en dos hemisferios simétricos) como paralelo “cero” de referencia. A partir de él, se avanza en grados sexagesimales en un sentido norte (° N) o sur (° S) dependiendo de si avanzamos hacia el hemisferio norte o el sur. Además del ecuador, existen cuatro paralelos notables: el círculo polar ártico (66° 33’ N), el trópico de Cáncer (23° 27’ N), el trópico de Capricornio (23° 27’ S) y el círculo polar antártico (66° 33’ S). Estas líneas sirven para determinar las zonas climáticas.

Estas líneas sirven para determinar las zonas climáticas.

Más en: Meridianos y paralelos

Dado que la Tierra no es del todo esférica, ni tiene realmente un arriba y un abajo, las representaciones que vemos de ella a diario no son del todo exactas en sus proporciones, sino que emplean escalas y procedimientos de proyección para construir una imagen verosímil, o sea, creíble, útil, del planeta. A estos procedimientos se les conoce como proyecciones geográficas, y a lo largo de la historia ha habido muchas de ellas y muy diferentes entre sí.

La más conocida de estas proyecciones, y la más empleada en la actualidad, es la proyección de Mercator, creada por el geógrafo flamenco Gerardus Mercator (1512-1594) en 1569. En ella se emplea un cilindro tangente al ecuador del planeta como patrón para representar la superficie, lo cual produce una necesaria distorsión en el largo de los paralelos, especialmente a medida que se aproximan a los polos.

Se ha criticado este modelo de mapamundi por ser eurocéntrico e invisibilizar al hemisferio sur, y existen numerosas propuestas de proyecciones alternativas, como la propuesta por el clérigo escocés James Gall (1808-1895) en 1855, pero dada a conocer más ampliamente por el cartógrafo alemán Arno Peters (1916-2002).

Más en: Proyecciones cartográficas

Mapamundi con placas tectónicas.Mapamundi político.Mapamundi político con países y ciudades.Mapamundi con accidentes geográficos continentales y oceánicos.Mapamundi en proyección de Robinson.Mapamundi en proyección de Mollweide.

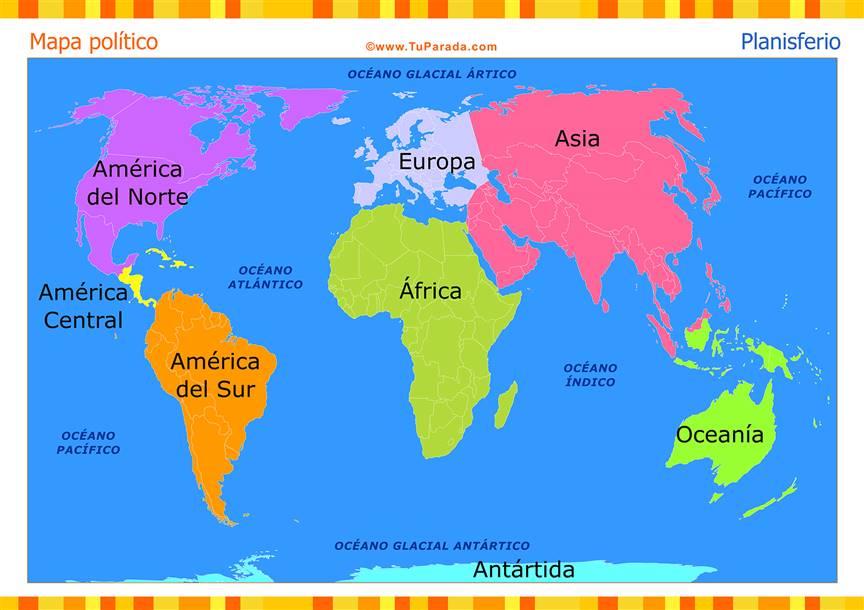

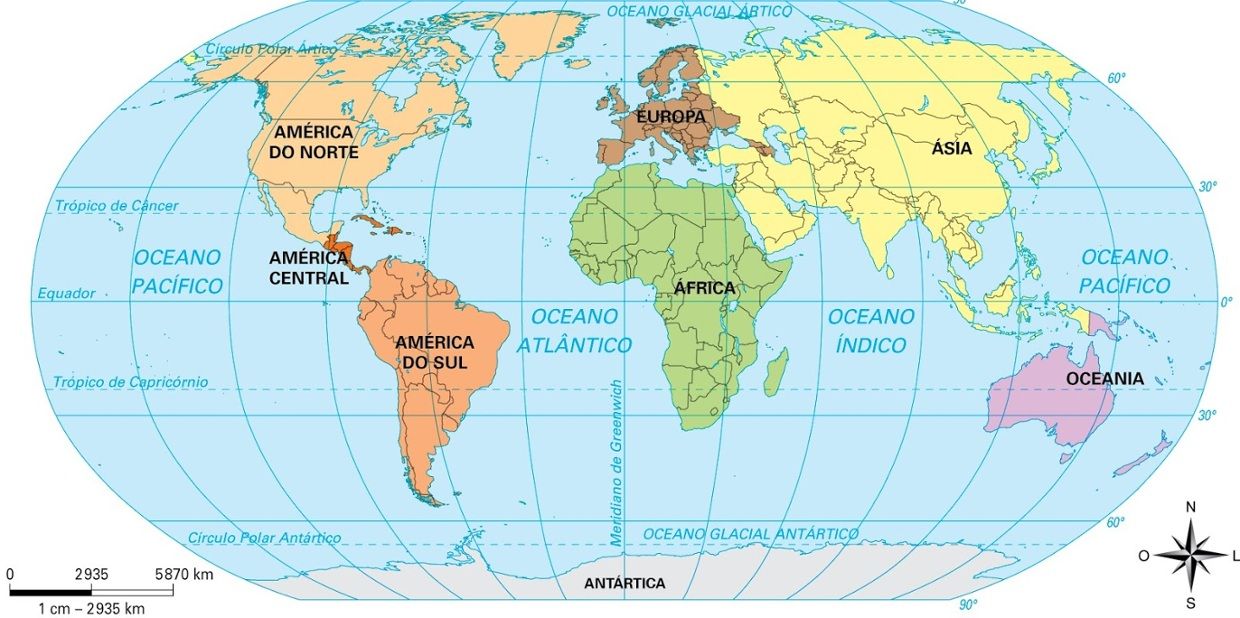

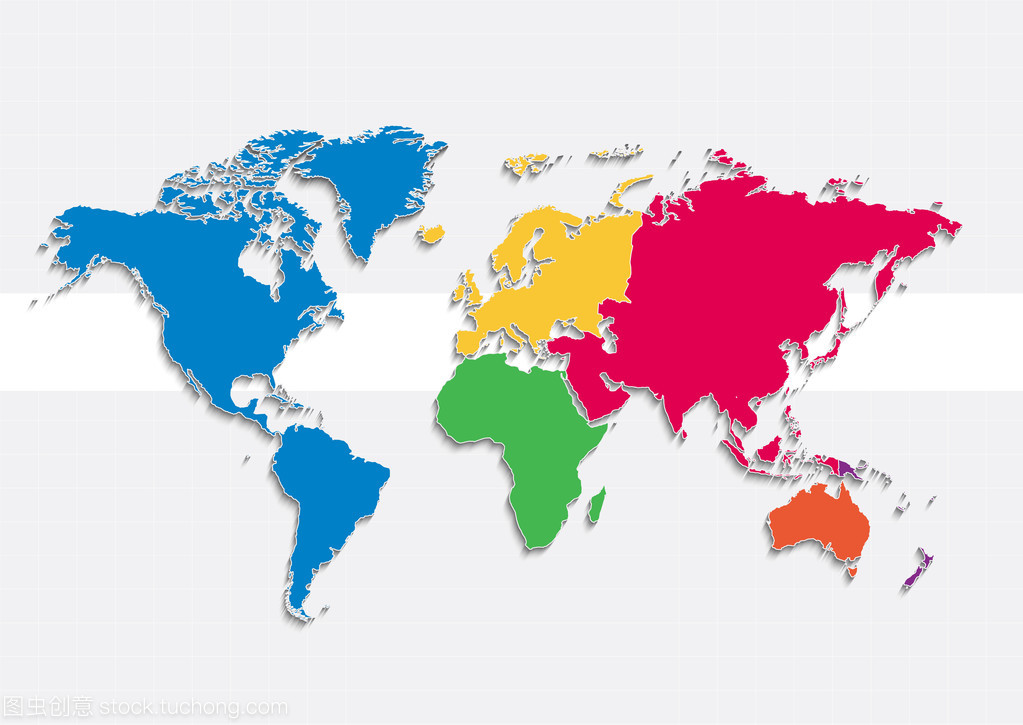

En el mapamundi aparecen los seis continentes del planeta:

Está ubicado al oeste de Europa y África, separado de ellos por el océano Atlántico y también de Asia por el océano Pacífico.

Está ubicado al oeste de Europa y África, separado de ellos por el océano Atlántico y también de Asia por el océano Pacífico.Más en: Continente

En el mapamundi aparecen los cinco océanos del planeta:

Más en: Océanos

Telegraph

Giovanni di Paolo (Giovanni di Paolo, 1403-1482), “Creation and Expulsion from Paradise” (1445). In this painting, the artist depicted the Earth as a classic T-O type map, surrounded by seven celestial spheres. By paradise is meant the Garden of Eden – an earthly paradise, the lower sphere of the Kingdom of Heaven

The eras of the early and classical Middle Ages in Europe (VI-XIV centuries) were the time of the dominance of monastic cartography. The monastic map, the so-called mappa mundi (“map of the world” in Latin), is a mixture of time and space, myths and realities of the Oikoumene known at that time. About 1100 monastery maps have survived to this day, about 600 of them were made before the 14th century.

The monastic map, the so-called mappa mundi (“map of the world” in Latin), is a mixture of time and space, myths and realities of the Oikoumene known at that time. About 1100 monastery maps have survived to this day, about 600 of them were made before the 14th century.

Most of the monastery maps are anonymous. They were produced in scriptoria, and the technology was identical to the creation of a book miniature. They were placed either on the walls of cathedrals and monasteries or in manuscripts, especially in psalter books, which is why they also received the name “psalter cards”, playing the role of literature for the illiterate (“pictura est laicorum litteratura”, that is, “painting is literature for the laity” in translation from Latin), just like icons or frescoes.

In addition to the educational function, maps of that time often served as an illustrative commentary on the writings of ancient and medieval authors who wrote about the Earth and those who inhabit it. Moreover, medieval cartographers placed special emphasis on eschatological themes, that is, on everything connected with the end of the world that awaits the earthly world. For example, in the bedroom of Adela Countess de Blois (Adela de Blois, Adela of Normandy, 1065–1138), daughter of William the Conqueror (William I the Conqueror, 1027–1087), there was a map illustrating the commentary of Beato de Liébana (c. 730 – after 798) Apocalypse.

Moreover, medieval cartographers placed special emphasis on eschatological themes, that is, on everything connected with the end of the world that awaits the earthly world. For example, in the bedroom of Adela Countess de Blois (Adela de Blois, Adela of Normandy, 1065–1138), daughter of William the Conqueror (William I the Conqueror, 1027–1087), there was a map illustrating the commentary of Beato de Liébana (c. 730 – after 798) Apocalypse.

According to the Holy Scriptures, the Earth is a flat disk washed by the Ocean. Above the Earth is the Sky, which rests on pillars and consists of two parts: the upper sky (“Heavenly Kingdom”) and the lower one (“celestial firmament”), to which the luminaries and stars are attached. At the northern end of the earthly world there were high mountains, behind which the Sun, revolving around the Earth, was hidden at night.

The main structural elements of medieval land descriptions, the authors of which were supporters of the planar form of the Earth, form a map of the so-called T-O type with an eastern orientation (east from above), where “T” is inscribed in “O”. Asia was placed on the upper, eastern part of the map. It was separated from the rest of the world by the horizontal lines of the Tanais (Don) and Nile rivers, as well as the Black, Azov, Aegean and Marmara seas. Accordingly, Europe on the map was on the left side and was separated from Africa, which was on the right, by the Mediterranean Sea. “O” is the circle of the earth itself.

Asia was placed on the upper, eastern part of the map. It was separated from the rest of the world by the horizontal lines of the Tanais (Don) and Nile rivers, as well as the Black, Azov, Aegean and Marmara seas. Accordingly, Europe on the map was on the left side and was separated from Africa, which was on the right, by the Mediterranean Sea. “O” is the circle of the earth itself.

T-O type map depicted as a book miniature in Isidore of Seville (San Isidoro de Sevilla, 560-636) “Etymology”, published in 1472. Reproduction from the archives of the Library of Congress USA

The arrangement of the continents in the form of the letter “T” was interpreted as a symbol of the frailty and doom of this world, since the “T” was the “Antonian cross” (without the upper ending), on which criminals were crucified in the southern and eastern provinces Roman Empire. Sometimes the cross was associated with Christ himself, and there are cards that place the world right on his body. One of the most famous maps of this type is the so-called Ebstorf Map, created in Lower Saxony in the middle of the 13th century. On such cards, on the sides of the head of the Savior, there were the letters A – “Alpha” and Ω – “Omega” with a comment from the Apocalypse: “I am the First and the Last” (1:7). Thus, the medieval monastery map turned into an eschatological model of the Universe, a kind of icon, which showed the beginning and end of the world.

On such cards, on the sides of the head of the Savior, there were the letters A – “Alpha” and Ω – “Omega” with a comment from the Apocalypse: “I am the First and the Last” (1:7). Thus, the medieval monastery map turned into an eschatological model of the Universe, a kind of icon, which showed the beginning and end of the world.

In the East, cartographers used to place paradise with Adam and Eve under the inscription: “And the Lord God planted paradise in Eden in the east; and placed there the man whom he had formed” (Gen. 2:8). There you can also see the tree of knowledge with the tempting serpent, the most cunning of “all the beasts of the field, which the Lord God created” (Genesis 3:1). The obligatory attribute of the East was the four rivers flowing from the heavenly lands. And on later maps, the scene of the Last Judgment was added here.

The most dramatic composition of these four elements is found on the famous Hereford map of the world (Hereford Mappa Mundi, c. 1290). Its creator, Richard of Haldingham and Lafford, depicted 12 winds outside the circle of the earth, and wrote the word MORS (“death” in Latin) in large letters around the perimeter to emphasize that human life is nothing more than a blade of grass carried by the wind through the mortal world in anticipation of death. The scene of the Last Judgment is especially impressive on Richard’s map, placed above to the right of the Savior, seated on a throne surrounded by angels and raising his hands in a prayerful pose with traces of nails. Nearby, angels lead the righteous out of the open graves. And on the right – demons drag sinners to the underworld.

1290). Its creator, Richard of Haldingham and Lafford, depicted 12 winds outside the circle of the earth, and wrote the word MORS (“death” in Latin) in large letters around the perimeter to emphasize that human life is nothing more than a blade of grass carried by the wind through the mortal world in anticipation of death. The scene of the Last Judgment is especially impressive on Richard’s map, placed above to the right of the Savior, seated on a throne surrounded by angels and raising his hands in a prayerful pose with traces of nails. Nearby, angels lead the righteous out of the open graves. And on the right – demons drag sinners to the underworld.

Eden with the sources of paradise rivers was usually separated from the inhabited Oikumene by the waters of the Ocean and other barriers. On the Ebstorf map, above the miniature depicting paradise, there is a comment: “Paradise and the tree of life, four rivers flowing from Paradise.” Under the head of Christ, between two streams of rivers, a more extensive legend is given, the source of which was the book of Genesis (2:8): This place is surrounded by a fiery wall up to the sky. There is a Tree of Life in Paradise, and whoever tastes the fruits from that tree will become immortal and is not afraid of old age. A spring originates here, which is divided into four branches, in Eden they flow underground, but outside Paradise they flow to the surface … Pishon (Ganges – I.F. ) flows out in India from Mount Ornobara … and flows into the Eastern Ocean; Geon (Nile – I.F. ) comes to the surface at Mount Atlas, then goes underground, appears at the Red Sea and flows into the Mediterranean near Alexandria, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers carry their waters to the Persian Gulf.

There is a Tree of Life in Paradise, and whoever tastes the fruits from that tree will become immortal and is not afraid of old age. A spring originates here, which is divided into four branches, in Eden they flow underground, but outside Paradise they flow to the surface … Pishon (Ganges – I.F. ) flows out in India from Mount Ornobara … and flows into the Eastern Ocean; Geon (Nile – I.F. ) comes to the surface at Mount Atlas, then goes underground, appears at the Red Sea and flows into the Mediterranean near Alexandria, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers carry their waters to the Persian Gulf.

Subsequently, many copies were broken around the question of the strange neighborhood of the Tigris and Euphrates with the Nile and the Ganges. But the paradox lies in the fact that from the point of view of modern science, their joint location on medieval maps is not so absurd. Nowadays, historians believe that the tributaries of the Euphrates, which dried up in ancient times, were called Pison and Geon (which, of course, they did not know about in the Middle Ages). According to scientists, the legend of Paradise Lost has quite historical roots. Probably, the Jews themselves borrowed the myth from the Sumerians, the people who created the first civilization in history in the interfluve of the Tigris and Euphrates 5000 years ago. For the Sumerians, the basis of the myth was an ecological catastrophe that occurred in this region about 7,000 years ago, when the waters of the Persian Gulf flooded a fertile region in southern Mesopotamia – according to some sources, the first agricultural oasis (in Sumerian, eden – “vegetated plain”). That is, the Garden of Eden rests at the bottom of the Persian Gulf in the territorial waters of Kuwait.

According to scientists, the legend of Paradise Lost has quite historical roots. Probably, the Jews themselves borrowed the myth from the Sumerians, the people who created the first civilization in history in the interfluve of the Tigris and Euphrates 5000 years ago. For the Sumerians, the basis of the myth was an ecological catastrophe that occurred in this region about 7,000 years ago, when the waters of the Persian Gulf flooded a fertile region in southern Mesopotamia – according to some sources, the first agricultural oasis (in Sumerian, eden – “vegetated plain”). That is, the Garden of Eden rests at the bottom of the Persian Gulf in the territorial waters of Kuwait.

Ebstorf map. Its creator is Gervasius Tilburiensis (Gervase of Tilbury, c. 1150–1228), abbot of the Ebstfor Monastery near Lüneburg in northwestern Germany. The original map was lost during World War II. At present, there are four copies of this manuscript made in the 19th century

From the 11th century, cartographers began to place Jerusalem at the center of the world, based on the words of the prophet Ezekiel (5:5): “Thus says the Lord God: this is Jerusalem! I have placed him among the nations, and around him are the lands. ” In the center of the Ebstorf map, the image of the city is accompanied by a legend:

” In the center of the Ebstorf map, the image of the city is accompanied by a legend:

Jerusalem is the most sacred capital of Judea… This most glorious city is the head of the whole world, for in Jerusalem the salvation of the human race was accomplished through the death and resurrection of the Lord, according to the words of the Psalmist: “My King from the Ages.” In this great city is the Holy Sepulcher, where the whole world strives in its piety.

On the Hereford map, Jerusalem also occupies a central place, and the scene of the Crucifixion is depicted above the city in the form of a kind of “compass rose”. The tradition of placing this city at the center of the inhabited world was so tenacious that we even meet it on the map of Heinrich Bunting (Heinrich Bunting, 1545-1606) from Magdeburg, famous for his atlas “Journey through the Holy Scriptures”, made in 1582.

An integral part of the medieval map of the world was also the image of the Antichrist and his associates – the impure peoples Gog and Magog. These peoples are mentioned three times in the Holy Scriptures, in particular in the Apocalypse: earth, Gog and Magog, and gather them for battle; their number is like the sand of the sea.

These peoples are mentioned three times in the Holy Scriptures, in particular in the Apocalypse: earth, Gog and Magog, and gather them for battle; their number is like the sand of the sea.

In the Qur’an these peoples are called Yajuj and Majuj (Sura XXI, 95-96; Sura XVIII). According to legend, Alexander Zulkarnain (Two-horned), aka Alexander the Great (‘Aλέξανδρος ο Μακεδών, 356–323), erected a huge wall of bronze, resin and sulfur, behind which he locked the barbarians Yajuj and Majuj until the Day of Judgment, when they break out on will. The appearance of the figure of Alexander the Great, who conquered all of Asia as far as India, automatically placed impure peoples not at the “four corners” of the earthly circle, but in the East.

With the appearance in Europe in 1241-1242 of the Mongol hordes of Batu Khan (1208-1255), who came from the depths of Asia, only confirmed this view and made the very topic of unclean peoples very relevant. The defeat of the German and Polish knights near Legnica on April 9, 1241 made many believe in the approach of the end of time. Even the English scholar Roger Bacon (c. 1214-1294), one of the most enlightened people of his time, advised paying as much attention as possible to the study of geography in order to accurately determine the time and direction of the invasion of the peoples of Gog and Magog.

Even the English scholar Roger Bacon (c. 1214-1294), one of the most enlightened people of his time, advised paying as much attention as possible to the study of geography in order to accurately determine the time and direction of the invasion of the peoples of Gog and Magog.

Planisphere by Andreas Walsperger (1415–?), 1448. In the lower left corner from the viewer there is a figure of an ogre devouring his victim with such passion that the anthropophagus’s hair stood on end. Reproduction by the author

Now their place of stay has been determined more precisely – near the Caspian Sea. So, on the Hereford map in an extensive legend east of the Caspian Sea (somewhere in the area of the modern Mangyshlak peninsula and the Ustyurt plateau), near a large ledge, which is cut off from the rest of the world by an impressive wall with four towers, it says:

Everything here is so terrible that it exceeds the limits of the probable: unbearable cold, constant harsh wind from the mountains, which the locals call “Biza”.

Very harsh people live here, they eat human flesh and drink blood, damned children of Cain. The Lord imprisoned them, having done this through Alexander the Great … In the time of the Antichrist, they will break out to the misfortune of the whole world.

Thus, the Caspian turned into one of the most disastrous places of that time. Perhaps this region was associated with Alamut, the fortress of the Assassins, a closed Ismaili order of cold-blooded killers.

But with the development of geographical knowledge and the establishment of relative stability in Asia in the XIV century, in the era of the Mongol Empire, the Caspian region no longer caused such fears, several branches of the Great Silk Road passed there, and European merchants, especially Italians, knew it well. The robber nest of Alamut was destroyed by the Mongols. The country of the Gog and Magog peoples moved further and further to the East, to the very Pacific Ocean (!).

But in the east of the Oikumene there were not only enemies, but also allies. And here it is appropriate to talk about the kingdom of Prester John, allegedly located somewhere in Asia. In search of allies to fight the Muslims, Pope Alexander III (Alexander III, 1105-1181) in 1177 sent a message to this mythical ruler with his personal physician. However, the messenger disappeared without a trace. Plano Carpini (Giovanni da Pian del Carpini, c. 1180-1252) and Marco Polo (Marco Polo, c. 1254-1324) believed that the kingdom of Prester John was located in the depths of Central Asia. It was later placed in Ethiopia. Belief in the existence of this Christian kingdom was so tenacious that the famous cartographer Abraham Ortelius (Abraham Ortelius, 1527-1598) in 1573 published a map entitled “Description of the Empire of Prester John or Abyssinia”.

And here it is appropriate to talk about the kingdom of Prester John, allegedly located somewhere in Asia. In search of allies to fight the Muslims, Pope Alexander III (Alexander III, 1105-1181) in 1177 sent a message to this mythical ruler with his personal physician. However, the messenger disappeared without a trace. Plano Carpini (Giovanni da Pian del Carpini, c. 1180-1252) and Marco Polo (Marco Polo, c. 1254-1324) believed that the kingdom of Prester John was located in the depths of Central Asia. It was later placed in Ethiopia. Belief in the existence of this Christian kingdom was so tenacious that the famous cartographer Abraham Ortelius (Abraham Ortelius, 1527-1598) in 1573 published a map entitled “Description of the Empire of Prester John or Abyssinia”.

Psalter map of the world in the middle of the 13th century. Reproduction by the author

In fact, the image of the Christian theocratic state was just a refraction of fragmentary information about the Nestorian principalities of the Central Asian peoples – Merkits, Naimans and Uighurs. Nestorianism was one of the trends in Christianity condemned as heresy at the Third Ecumenical Council of Ephesus in 431. His adherents considered Jesus a man, thanks to his virtues, elevated to divinity, but not a God-man, which was advocated by Catholics and Orthodox. Some Uighur or Merkit princelings were indeed Christians, but they were not high priests. Moreover, Christianity was not considered the only true religion here. In Europe, they had no idea that they were asking for help from heretics. However, the contact of the two Christian traditions did not take place. After the Mongol conquest in the 13th century, Central Asian Christianity fell into decline.

Nestorianism was one of the trends in Christianity condemned as heresy at the Third Ecumenical Council of Ephesus in 431. His adherents considered Jesus a man, thanks to his virtues, elevated to divinity, but not a God-man, which was advocated by Catholics and Orthodox. Some Uighur or Merkit princelings were indeed Christians, but they were not high priests. Moreover, Christianity was not considered the only true religion here. In Europe, they had no idea that they were asking for help from heretics. However, the contact of the two Christian traditions did not take place. After the Mongol conquest in the 13th century, Central Asian Christianity fell into decline.

Many people are accustomed to looking at the maps of the classical Middle Ages as geographic misunderstandings. Of course, there was no exact scale and degree grid, which appeared in the late Middle Ages (XV-XVII centuries). But it must be said that even this did not free geography from the pursuit of ghosts. It’s just that imaginary realities have become more “scientific”. Even on the maps of the New Age, there are a huge number of islands that were discovered and then lost. So, in 1762, Spanish sailors from the Aurora discovered three new islands southwest of the Falkland Islands. Their coordinates were accurately fixed – 52 ° 37′ south latitude and 47 ° 49´ west longitude. A few years later, the information was confirmed by the captain from another Spanish ship, the San Miguel. In 1794, the third Spanish crew from the Artevido corvette sailed past them again. However, since 1856, all attempts to find this small archipelago ended in failure. Only a decade later, in the 1870s, the ghost islands disappeared from the charts.

It’s just that imaginary realities have become more “scientific”. Even on the maps of the New Age, there are a huge number of islands that were discovered and then lost. So, in 1762, Spanish sailors from the Aurora discovered three new islands southwest of the Falkland Islands. Their coordinates were accurately fixed – 52 ° 37′ south latitude and 47 ° 49´ west longitude. A few years later, the information was confirmed by the captain from another Spanish ship, the San Miguel. In 1794, the third Spanish crew from the Artevido corvette sailed past them again. However, since 1856, all attempts to find this small archipelago ended in failure. Only a decade later, in the 1870s, the ghost islands disappeared from the charts.

But there are also opposite cases. First of all, this concerns the famous map of the Turkish admiral and cartographer Piri Reis (Piri Reis, Hadji Muhiddin Piri Ibn Hadji Mehmed, 1465–1555). At 19On 29, in the library of the Sultan’s Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, a part of the manuscript was discovered, which was a sea map of the Atlantic Ocean with the coasts of Africa, America and the north of Antarctica, made by Admiral Reis, which was confirmed by a graphic examination. The time of drawing up the map is 1513. The analysis of paints and parchment gave a confirming result. The discovery immediately attracted the attention of scientists – after all, it is believed that Antarctica was discovered only in 1820! But the researchers were even more astonished when they realized that Piri Reis depicted the ice-free coastline of the Antarctic Queen Maud Land, although geologists estimate the age of the South Pole ice at 25 million years!

The time of drawing up the map is 1513. The analysis of paints and parchment gave a confirming result. The discovery immediately attracted the attention of scientists – after all, it is believed that Antarctica was discovered only in 1820! But the researchers were even more astonished when they realized that Piri Reis depicted the ice-free coastline of the Antarctic Queen Maud Land, although geologists estimate the age of the South Pole ice at 25 million years!

The accuracy of the geographical details on the mysterious map was confirmed in the 1940s and 50s after a seismic survey of this area of Antarctica.

Here is an excerpt from the commander of the 8th Technical Intelligence Squadron, US Air Force Strategic Command, Lieutenant Colonel Harold Olmeira, dated July 6, 1960:

Swedish-British Antarctic Expedition at 1949 year. This means that the mapping of the coastline was made before the glaciation. The glacier in this area is currently one mile thick.

We do not see how the data of this map can be reconciled with the supposed level of geographical science in 1513.

Piri Reis map. Reproduction from the archive of the Cartography Department of the Turkish Army

It is curious that on his map the admiral depicted not only clear coastlines of three continents, but also fabulous animals, in the best traditions of medieval cartography. On the lands of Antarctica he signed:

White-haired monsters seem to exist in this country, as well as six-horned cattle. the Portuguese pagans wrote it down in their maps… This country is a desert. Everything is in ruins, and it is said that large snakes have been found there. That is why the Portuguese pagans did not land on these shores, and they are also said to be very hot (!).

Scientists still can not put forward any plausible version that is compatible with the assumption of the authenticity of Reis’ map. To do this, we must admit that, firstly, the age of the Antarctic ice cannot be measured either in millions or even hundreds of thousands of years, and, secondly, that already before 4000 BC. there was already a civilization on earth that possessed mapping skills at a level that Europe reached only in the 18th century. 4000 BC – this is the time of the appearance of the first civilizations in Mesopotamia and Egypt. Otherwise, the representatives of the lost protocivilization simply had no one to pass on their secrets to. Both of these assumptions contradict the available scientific data.

To do this, we must admit that, firstly, the age of the Antarctic ice cannot be measured either in millions or even hundreds of thousands of years, and, secondly, that already before 4000 BC. there was already a civilization on earth that possessed mapping skills at a level that Europe reached only in the 18th century. 4000 BC – this is the time of the appearance of the first civilizations in Mesopotamia and Egypt. Otherwise, the representatives of the lost protocivilization simply had no one to pass on their secrets to. Both of these assumptions contradict the available scientific data.

Curiously, the Piri Reis map is not the only one that shows Antarctica without an ice cap. The Library of Congress in Washington DC holds a map of Orontius Fineus (1494–1555) dated 1531. It displays the entire coastline of the southern mainland, which is generally consistent with the data of geologists. And in 1737, Philippe Buache (Philippe Buache, 1700-1773) published a map in Paris, which depicted the entire southern continent. The most interesting thing is that on the Buache map it was presented as two islands separated by a large strait. The presence of a large body of water in the center of Antarctica has also been confirmed.

The most interesting thing is that on the Buache map it was presented as two islands separated by a large strait. The presence of a large body of water in the center of Antarctica has also been confirmed.

It is also embarrassing that all the documents named by the authors of these three maps as sources of information, for some reason, disappeared without a trace … This cannot but inspire skepticism, but the fact of forgery has not yet been recorded.

Igor Fomenko

View of New Castile. Province of Guadalajara

The sands of Maspalomas on the island of Gran Canaria remind of the closeness of Africa

Antiquity and the early Middle Ages

Rock paintings in the cave of Altamira. Late Paleolithic

Settlement of the Santa Tecla Galaik tribe. Galicia. 1st century BC e. – I century. n. e.

Votive crown of the Visigoth king Recesvint. 7th century National Archaeological Museum, Madrid

7th century National Archaeological Museum, Madrid

Mosaic with the Judgment of Paris scene from a Roman villa in Casarice (Seville). 4th century n. e.

Temple of Diana. Merida. 1st century n. e.

Art of al-Andalus

Dome in the Hall of Ambassadors of the Alcazar of Seville. Mudéjar style. 15th century

Interior of the Grand Mosque in Cordoba. Second half of the 8th-10th centuries

Interior of the Grand Mosque in Cordoba. Mihrab. X century

Aljaferia Palace in Zaragoza. North facade. 11th century

Myrtle courtyard in the Nasrid palace. Alhambra. 14th century

Mosque of Cristo de la Luz in Toledo (Muslim name Bab al-Madrum). End of the 10th century

Pre-Romanesque

San Miguel de Lillo. 9th century Oviedo

Santa Cristina de Lena. Interior. 9th century Asturias

Victory Cross. Gift of Alfonso III to the Cathedral of San Salvador in Oviedo. 10th century Treasury of the Cathedral

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Beat of Valcavado. X century Library of the University of Valladolid

Beat of Valcavado. X century Library of the University of Valladolid

Mapa mundi. Beat of Saint Sever, 1050 National Library of France, Paris

Spanish Romanic

Romanesque capital. Cloister of the Monastery of Sant Cugat del Valles. Prov. Barcelona

Collegiate Church of Santa Maria la Mayor in Toro. 12th century

Transept of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. 12th century

Romanesque portal of the Church of Santa Maria la Real in Sanguez. 12th century

Statue of the Virgin Mary – Flight from Egypt. XII-XIV centuries Museum of Ancient Art, Siguença

Pantocrator. Fresco from the apse of the Church of San Climen de Taul. OK. 1223 National Museum of Catalonia, Barcelona

Pantocrator. 12th century Fresco in the Royal Pantheon of the Collegiate Church of San Isidro, León

Spanish Gothic

Virgin Mary. Portal of the main facade of the cathedral in Tarragona. 13th century

Gargoyle of the Cathedral of Palencia. XIV-XV centuries

XIV-XV centuries

Portal of the Sarmental Cathedral in Burgos. 1230–1240

Medieval book miniature

Initial in manuscript. End of the 10th-11th century

Alfonso III and his wife, Queen Ximena. Liber Testamentorum. Oviedo. 12th century

Pilgrims’ meal. Cantigui Alfonso X. XIII c.

Medieval artist at work. Cantigui Alfonso X. XIII c.

Scribe. Game book. 13th century

Construction of a church. Work on the decoration of the nave of the church. Cantigui Alfonso X. XIII c.

World of the Spanish aristocracy

Gravestone of the Marquises of Senete. Fragment. Mid 16th century Dominican monastery. Valencia

Gravestone of Fernand Pérez de Andrade. End of the 14th century Church of San Francisco, Betanzos

Iñigo López de Mendoza, Marquis of Santillana. Detail of a mid-15th century retablo. Artist Jorge Ingles. Collection of the Dukes of Infantado. Exhibited at the Prado Museum, Madrid

Juan Pantoja de la Cruz. Portrait of Diego de Villamayor. 1605 Hermitage, St. Petersburg

Portrait of Diego de Villamayor. 1605 Hermitage, St. Petersburg

Villena Castle in the province of Alicante in the middle of the 15th century. belonged to the powerful family of Pacheco

The Manzanares castle north of Madrid is an example of the Spanish-Flemish style. Architect Juan de Guas. 1475 – end of the 15th century

The Palace of the Dukes of Medinaceli in Cogoludo is one of the first examples of Renaissance architecture in Spain. Architect Lorenzo Vazquez. Between 1492 and 1502

Epoch of the Catholic Kings

Madonna of the Catholic Kings. Circle Master Fernando Gallego. Between 1490 and 1493 Prado, Madrid

Heraldic decoration of the wooden ceiling in the gallery of the monastery of San Juan de los Reyes. Toledo. End of the 15th century

Alcazar of Segovia – one of the favorite residences of the Catholic kings

Isabella’s crown and scepter, Fernando’s sword. Royal Chapel, Granada

Bartolome Bermejo. Pieta of Canon Desplat. 1490 Barcelona Cathedral Museum

Pieta of Canon Desplat. 1490 Barcelona Cathedral Museum

16th century

El Greco. The funeral of Senor Orgaz. 1586–1588 Church of Santo Tome, Toledo. Fragment

Toledo in the second half of the 16th century. Engraving from the book “Civitates orbis terrarum”

Construction of the Escorial. Drawing of the second half of the 16th century.

El Greco. View of Toledo. 1610–1614 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

17th century

Don Juan Francisco Pimentel, tenth count of Benavente. OK. 1648 Diego Velasquez. Prado, Madrid

Diego Velasquez. Water seller in Seville. OK. 1619 Wellington Museum, London

Juan Bautista Martinez del Maso. View of Zaragoza. 1646 Prado, Madrid

Antonio de Pereda. The dream of a caballero. 1655 Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, Madrid

Bartolome Esteban Murillo. Lousy. OK. 1645 Louvre, Paris

Francisco Zurbaran. Saint Francis. 1634 Milwaukee Art Museum

History painting

St.