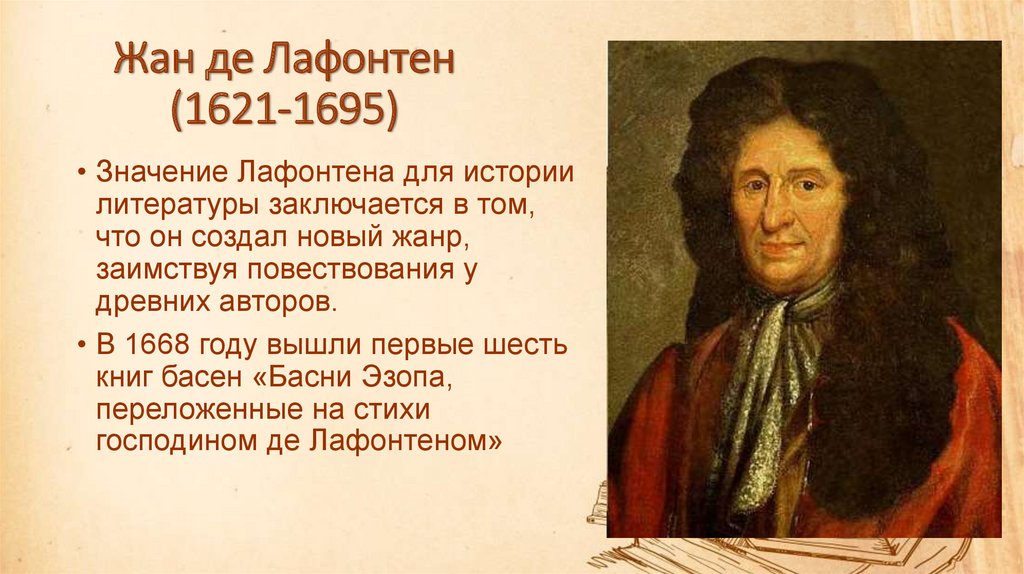

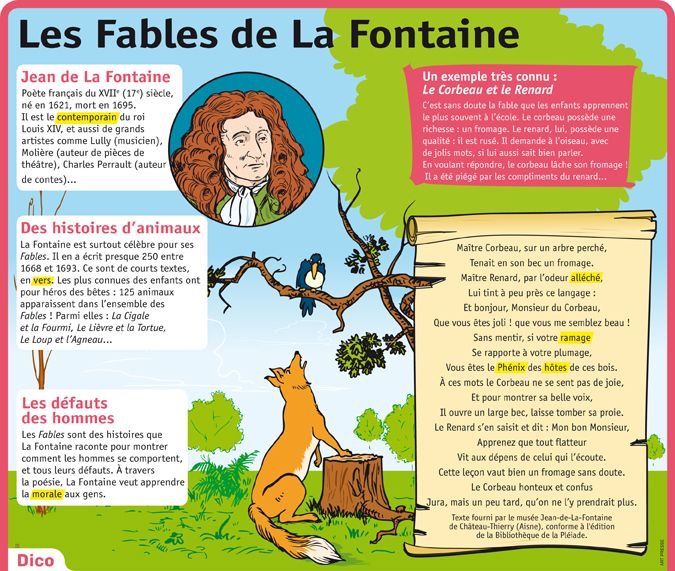

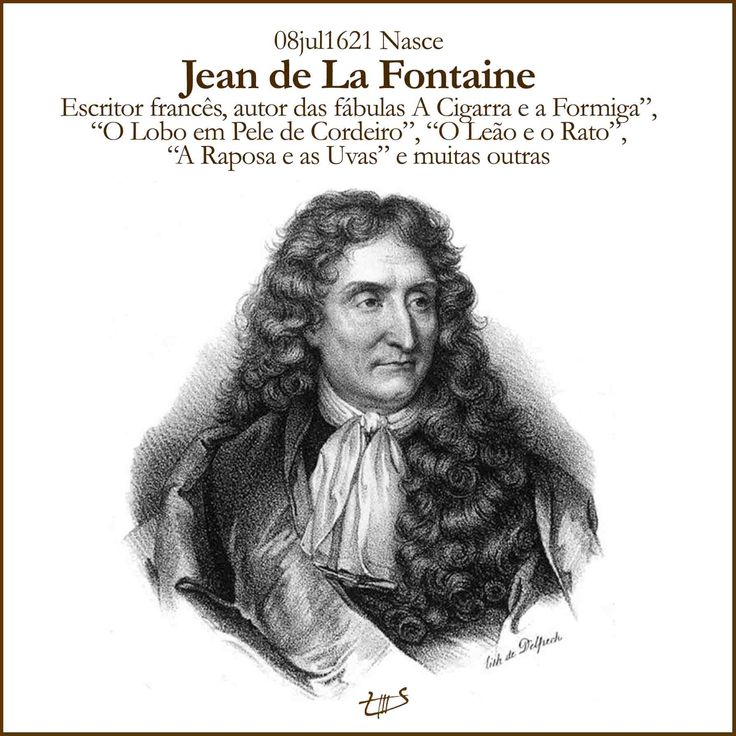

Aunque se considera a Esopo como el primer fabulista y, por lo tanto, iniciador de este tipo de relatos breves protagonizados por animales, con una moraleja final; Jean de la Fontaine es asimismo uno de los más conocidos fabulistas de todos los tiempos.

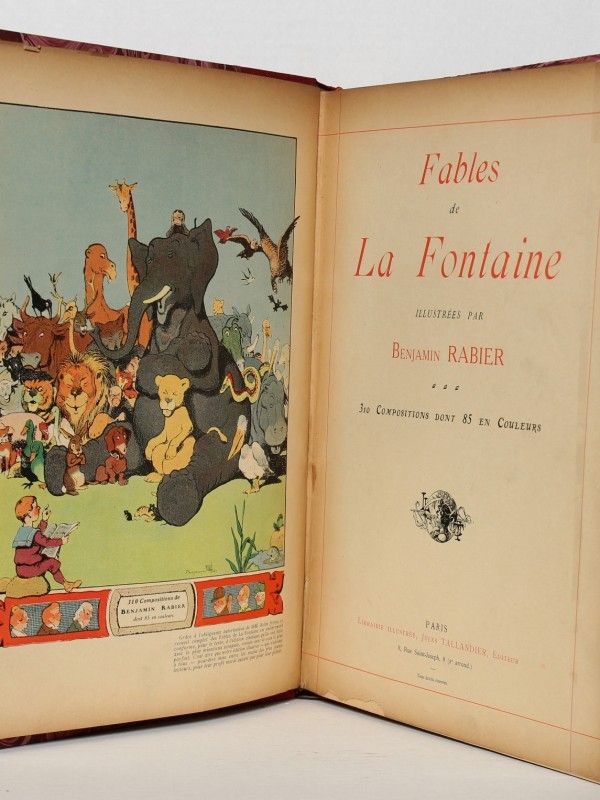

Este escritor francés del siglo XVII escribió 243 fábulas en forma de poema, en ellas recoge temas que ya había tocado Esopo pero, le intenta dar un toque más moderno y actual a su época, tal y como él mismo indica en el prólogo de su obra.

Las fábulas son un estupendo recurso para educar a los niños en valores, al mismo tiempo que mostrarles el placer por leer e iniciarles en la lectura de la poesía. Te invitamos a leer esta selección de bellas fábulas para niños de Jean de la Fontaine, son cuentos cortos con los que tuvo mucho éxito en su época y aun hoy son leídas.

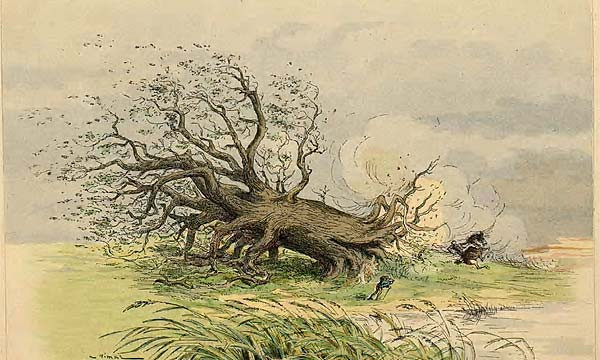

Dijo la Encina a la Caña:

– ¡Cuánta razón tienes para quejarte de la naturaleza!. Un pajarillo es para ti un enorme peso; la brisa más ligera, que riza la superficie del agua, te hace inclinar la cabeza. Por el contrario, mi copa no sólo detiene los rayos del sol; sino que también desafía a la tempestad. Para ti, todo es vendaval ; para mí, brisa suave. Si nacieses, a lo menos, al abrigo de mi follaje, no padecerías tanto: yo te defendería de la borrasca. Pero casi siempre brotas en las húmedas orillas del reino de los vientos. ¡Injusta ha sido contigo la naturaleza!

– Tu compasión, respondió la Caña, prueba tu buena naturaleza; pero no te apures. Los vientos no son tan temibles para mí como para ti. Me inclino y me doblo, pero no me quiebro. Hasta el presente has podido resistir las mayores ráfagas sin inclinar el espinazo; pero nadie es dichoso hasta el final.

Apenas dijo estas palabras, de los confines del horizonte acude furibundo el más terrible huracán. El árbol resiste, la caña se inclina; el viento redobla sus esfuerzos, y tanto sopla y sopla, que al fin arranca de cuajo a la Encina.

Moraleja: ante la adversidad y los problemas, el soberbio cae y el humilde resiste.

Lee esta fábula en verso

Había una vez unos panales de miel que parecían no tener dueño. Los zánganos los reclamaban, pero las abejas se oponían a que se quedaran con ellos. Así que decidieron llevarlos al tribunal de la avispa juez.

Cuando comenzó el juicio para ver quién se quedaba con los panales, no parecían ponerse de acuerdo. Algunos testigos decían haber visto volando alrededor de aquellos panales algunos insectos parecidos a las abejas, pero claro, los zánganos y las abejas son muy parecidos.

La avispa juez, viendo que no había acuerdo, decidió abrir un juicio y llamar a declarar a todo el hormiguero, pero ni por esa spudo aclarar la duda.

– ¿Qué pasa aquí?, ¿Me queréis decir a qué viene todo esto?, preguntó una abeja muy avispada.

– Seis meses hace ya que está pendiente el problema y estamos como el primer día, continuó. Mientras tanto la miel se está perdiendo ya es hora de que el juez se decida. Bastante ha tardado ya. Trabajemos los zánganos y nosotras, las abejas, y veremos quién sabe hacer panales tan buenos y tan repletos de rica mie.

Mientras tanto la miel se está perdiendo ya es hora de que el juez se decida. Bastante ha tardado ya. Trabajemos los zánganos y nosotras, las abejas, y veremos quién sabe hacer panales tan buenos y tan repletos de rica mie.

Los zánganos no admitieron aquella propuesta, y con ello, demostraron que el arte de hacer panales era más propio de las abejas y, en definitiva, era superior a sus habilidades.

Así fue como la avispa jueza dio la razón a las abejas, quienes quedaron como auténticas dueñas del panal y, por supuesto de la miel.

Moraleja: Por la obra se conoce al artesano.

Lee esta fábula de La Fontaine en verso

Con esta fabulita quiero haceros ver cuán insignificantes e innecesarias son a veces las palabras de los necios…

Un buen día, un niño que estaba jugando a orillas del río Sena, cayó al agua. Por suerte para el pequeño, justo al lado del lugar donde había caído, habían crecido unas ramas que fueron su salvación.

Agarrado estaba a ellas, cuando vio pasar a un maestro de escuela, y aliviado el niño gritó:

– ¡Socorro, que muero!, ayúda, sálveme señor.

El maestro, oyendo los gritos, se volvió hacia el niño y, adoptando una postura muy tiesa y un tono de voz muy grave y serio, le reprendió:

– ¿Habráse visto pillastre como este?, esto es inaudito. Mira en qué apuro te ha puesto tu atolondramiento, pequeño granuja, iba diciendo el maestro.

– Que tenga yo que encargarme y enseñar a calaverillas como éste… ¡Qué desgraciados son los padres que tienen que cuidar de tan malos hijos! ¡Bien dignos son de lástima!, seguía insistiendo el maestro, mientras el niño continuaba asustado y agarrado a las ramas.

Una vez terminado el largo discurso, sacó al asustado muchacho a la orilla.

Y aquí, es donde lanzo mi crítica a muchos más de los que se sienten aludidos. Todos ellos charlatanes, criticones, pedantes y censores que pueden reflejarse en este pequeño relato. Todos ellos forman un gran número, y es que sin duda, Dios hizo fecunda a esta raza.

¡No hay tema sobre el que no piensen ejercer su habladuría! ¡Siempre tienen una crítica que hacer!

¡Pero amigo, líbrame del apuro primero, y después suelta tu lengua!

Lee esta fábula en verso y haz unos ejercicios de comprensión lectora

Había una vez un Lobo, y estaba tan flaco, que no tenía más que piel y huesos. Y es que, los perros andaban tan vigilantes del ganado que no había opción a llevarse comer un tierno corderito.

Un buen día, encontró a un mastín, rollizo y lustroso, que se había extraviado. La primera idea que se le cruzó fue la de apresarlo y comerlo, eso es cosa que hubiese hecho de buen grado el señor lobo. Pero había que emprender batalla contra el enorme perro, y el enemigo tenía trazas de defenderse bien, además, se sentía cansado y falta de energía debido al hambre.

El lobo se le acerca con la mayor cortesía, e inicia una conversación con él, felicitándole por sus buenas carnes.

– No estáis tan lucido como yo, porque no queréis, contesta el perro. Deja el bosque; los vuestros, que en él se guarecen, son unos desdichados, muertos siempre de hambre. ¡Ni un bocado prueban al día, seguro! ¡Todo a la ventura! ¡Siempre a la espera de lo que caiga! Sígueme, y tendrás mejor vida.

– ¿Y qué tendré que hacer?, preguntó el lobo.

– Casi nada, respondió el perro, asustar a los ladrones y a los que llevan bastón o garrote; acariciar a los de casa, y complacer al amo. Con tan poco como es esto, tendrás comida diaria seguro. Yo me nutro con las sobras de todas las comidas, huesos de pollos y pichones; y además, si me porto bien, obtengo algunas caricias, por añadidura.

El Lobo, que escucha todas estas lindezas sobre la vida del perro en la granja, se imagina un porvenir de gloria, comida todos los días, cuidados y, de pensarlo, lloró de alegría.

Comenzó a caminar hacia la granja con el perro pero advirtió que su nuevo compañero tenía en el cuello una peladura.

– ¿Qué es eso? preguntó.

– Nada, dijo el perro sin mirarle a los ojos

– ¡Cómo nada!, insistió el lobo

– Poca cosa, se negaba a confesar el perro.

-Algo será, no dándose por vencido el lobo.

– Será la señal del collar a que estoy atado, confesó por fin el mastín.

– ¡Atado! exclamó el Lobo, pero.. ¿qué?, ¿no vas y vienes a donde queréis y cuando quieres?

– No siempre, pero eso, ¿qué importa?, dijo el perro restándole importancia.

– Importa tanto, que renuncio a vuestra comida, techo y caricias, ya que de ir contigo renunciaría al mayor tesoro, dijo, y echó a correr.

Aún está corriendo.

Moraleja: La libertad es nuestro mayor tesoro, no debemos venderla a cualquier precio.

Preguntas para reflexionar sobre esta fábula

La zorra simempre había comentado ante los demás animales que la cigüeña era muy boba, le gustaba mofarse de ella y un buen día, decidió ir un poco más allá de los insultos y quiso hacerle una broma.

La invitó a cenar a su casa y preparó una deliciosa comida que dispuso sobre una mesa bien adornada. Cuando llegó la cigüeña, sintió que el dulce aroma de los alimentos le abría el apetito pero…

Al senarse a la mesa, se dio cuenta de que la zorra había puesto toda la comida en platos muy grandes y llanos, así que, no podía llevarse ni un solo bocado porque su largo y fino pico le impedía degustar tan ricas viandas.

Sin embargo, la cigüeña no protesó, miró a la zorra, le agradeció la invitación y se fue. Y allí quedó la zorra, muerta de la risa.

Pocos días después, ambos se volvieron a encontrar cerca del estanque, y en esta ocasión, fue la cigüeña la que invitó a cenar a la zorra. La zorra aceptó de buen gusto y pensó para sí:

“Esta cigüeña sigue siendo tan boba, que incluso después de lo que pasó en mi casa, sigue queriéndome agradecer la invitación”.

La cigüeña había trabajado mucho para preparar una comida exquisita y, a la hora indicada, la zorra se presentó en su casa dispuesta a comer los alimentos que había preparado la cigüeña. La zorra comenzó a salivar al percibir los exquisitos olores que llegaban de la cocina y se sentó rápidamente a la mesa, para poder dar cuenta de las viandas. Pero, cuando se sentó en la mesa, se dio cuenta de que todos los alimentos estaban servidos en tarros y vasijas de cuello muy largo, tanto que solo cabía el pico de una cigüeña, y no el hocico de una zorra.

La zorra comenzó a salivar al percibir los exquisitos olores que llegaban de la cocina y se sentó rápidamente a la mesa, para poder dar cuenta de las viandas. Pero, cuando se sentó en la mesa, se dio cuenta de que todos los alimentos estaban servidos en tarros y vasijas de cuello muy largo, tanto que solo cabía el pico de una cigüeña, y no el hocico de una zorra.

La cigüeña comenzó a comer con apetito y, cuando hubo terminado, le dijo a la zorra que la miraba con disgusto:

– ¿Ves? Es una comida tan sabrosa como la que tu preparaste.

Moraleja: no hagas nunca a los demás lo que no quieres que te hagan a ti, y también puede extraerse una segunda moraleja, donde las dan, las toman.

Recursos para trabajar en el aula esta fábula

La cigarra era feliz disfrutando del verano: El sol brillaba, las flores desprendían su aroma…y la cigarra cantaba y cantaba. Mientras tanto su amiga y vecina, una pequeña hormiga, pasaba el día entero trabajando, recogiendo alimentos.

– ¡Amiga hormiga! ¿No te cansas de tanto trabajar? Descansa un rato conmigo mientras canto algo para ti. ? Le decía la cigarra a la hormiga.

– Mejor harías en recoger provisiones para el invierno y dejarte de tanta holgazanería ? le respondía la hormiga, mientras transportaba el grano, atareada.

La cigarra se reía y seguía cantando sin hacer caso a su amiga.

Hasta que un día, al despertarse, sintió el frío intenso del invierno. Los árboles se habían quedado sin hojas y del cielo caían copos de nieve, mientras la cigarra vagaba por campo, helada y hambrienta. Vio a lo lejos la casa de su vecina la hormiga, y se acercó a pedirle ayuda.

– Amiga hormiga, tengo frío y hambre, ¿no me darías algo de comer? Tú tienes mucha comida y una casa caliente, mientras que yo no tengo nada.

La hormiga entreabrió la puerta de su casa y le dijo a la cigarra.

– Dime amiga cigarra, ¿qué hacías tú mientras yo madrugaba para trabajar? ¿Qué hacías mientras yo cargaba con granos de trigo de acá para allá?

– Cantaba y cantaba bajo el sol- contestó la cigarra.

– ¿Eso hacías? Pues si cantabas en el verano, ahora baila durante el invierno-

Y le cerró la puerta, dejando fuera a la cigarra, que había aprendido la lección.

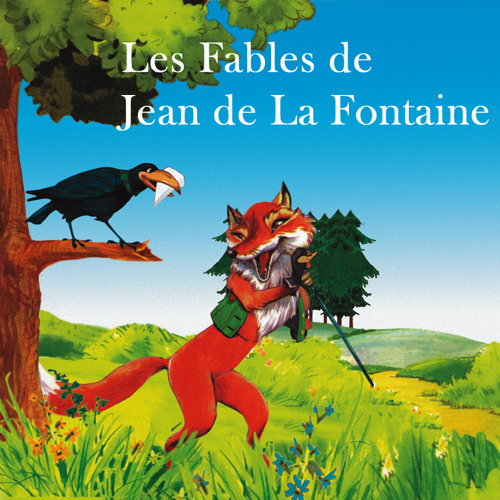

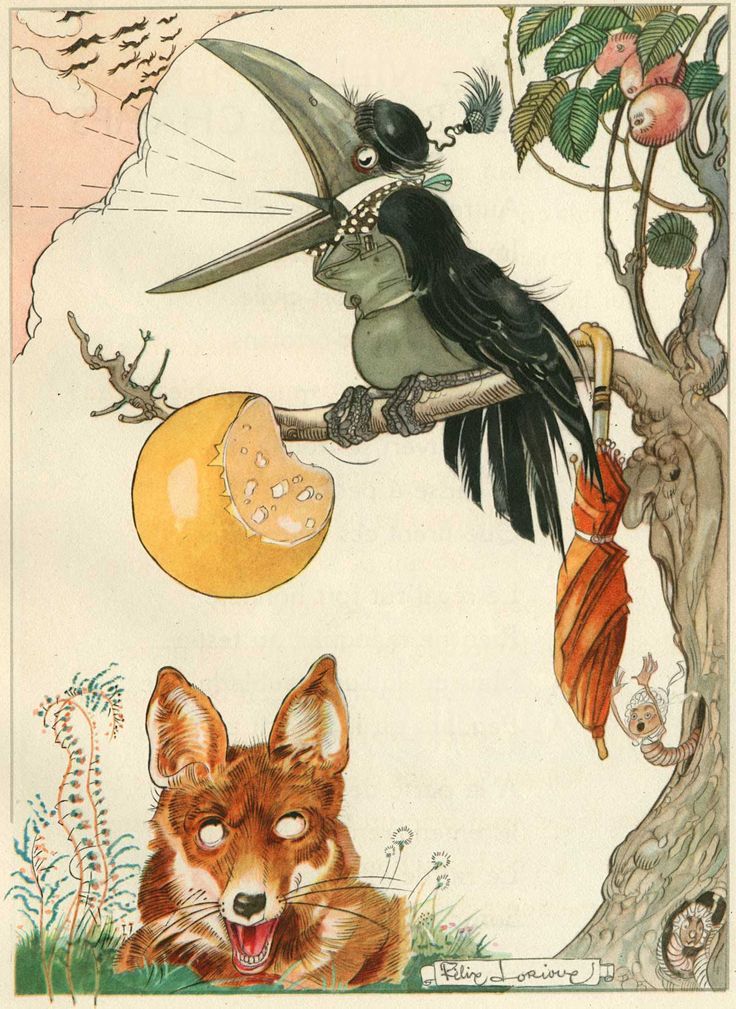

Estaba un señor Cuervo posado en un árbol, y tenía en el pico un queso. Atraído por el tufillo, el señor Zorro le habló en estos o parecidos términos:

– ¡Buenos días, caballero Cuervo! ¡Gallardo y hermoso eres en verdad! Si el canto corresponde a la pluma, os digo que entre los huéspedes de este bosque tu eres el Ave Fénix”.

El Cuervo al oír esto, no cabía en la piel de gozo, y para hacer alarde de su magnífica voz, abrió el pico, dejando caer la presa.

La tomó el Zorro y le dijo: “Aprended, señor mío, que el adulador vive siempre a costas del que le atiende; la lección es provechosa; bien vale un queso”.

El Cuervo, enfadado, juró, aunque algo tarde, que no caería más en la trampa.

Moraleja: no te fíes de las alabanzas y elogios de los demás. No confíes en quien solo te ensalza.

No confíes en quien solo te ensalza.

Lee esta fábula en inglés

Vio cierta Rana a un Buey, y le pareció bien su corpulencia. La pobre no era mayor que un huevo de gallina, y quiso, envidiosa, hincharse hasta igualar en tamaño al fornido animal.

– Mirad, hermanas, decía a sus compañeras; ¿es bastante? ¿No soy aún tan grande como él?

? No.

? ¿Y ahora?

? Tampoco.

? ¡Ya lo logré!

? ¡Aún estás muy lejos!

Y el infeliz animal se hinchó tanto, que reventó.

Moraleja: Lleno está el mundo de gentes que son avisadas y aun así chocan de frente con el peligro. La rana no quiso aceptar lo que era, y en su intento de ser como el buey, murió la infeliz.

Menú

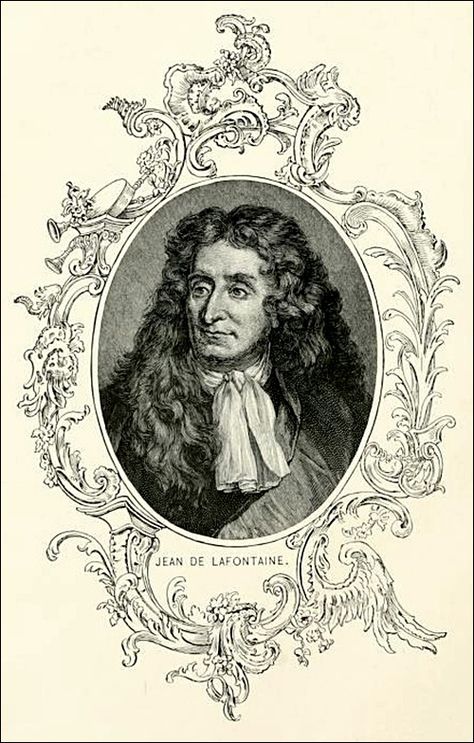

En 1621, nació en una ciudad de Francia, Jean de la Fontaine siendo el primogénito de un consejero del rey a quien se le había dado la tarea de ocuparse de los bosques y de la caza de su palacio. A los catorce años fue enviado a París para que ingresara a una orden religiosa, sin embargo la abandonó poco después y decidió comenzar a estudiar derecho. Consiguió un trabajo parecido al de su padre y en el tiempo libre que tenía se dedicó tranquilamente a la escritura. Redactó doce libros de fábulas que son conocidas en todas las partes del mundo. Las fábulas de La Fontaine no se caracterizan por su brevedad, sino por el enriquecimiento de las narraciones a las que aportó un toque de elegancia. Versionó varias fábulas conocidas de Esopo y de Fedro. Murió a los setenta y cuatro años en París.

A los catorce años fue enviado a París para que ingresara a una orden religiosa, sin embargo la abandonó poco después y decidió comenzar a estudiar derecho. Consiguió un trabajo parecido al de su padre y en el tiempo libre que tenía se dedicó tranquilamente a la escritura. Redactó doce libros de fábulas que son conocidas en todas las partes del mundo. Las fábulas de La Fontaine no se caracterizan por su brevedad, sino por el enriquecimiento de las narraciones a las que aportó un toque de elegancia. Versionó varias fábulas conocidas de Esopo y de Fedro. Murió a los setenta y cuatro años en París.

Los dos gallos

La garza real

Los dos amigos

El zapatero y el millonario

El león enfermo y los zorros

La mochila

El asno y el caballo

Alegre le mostraba su espacio adornado con decoraciones traídas del extranjero y un banquete muy bien servido, el cual no pudieron tomar con tranquilidad cuando empezaron a ser perseguidos por el gato del lugar. El ratón de campo permaneció espantado y prefirió que fueran a su hogar para continuar con la cena.

Alegre le mostraba su espacio adornado con decoraciones traídas del extranjero y un banquete muy bien servido, el cual no pudieron tomar con tranquilidad cuando empezaron a ser perseguidos por el gato del lugar. El ratón de campo permaneció espantado y prefirió que fueran a su hogar para continuar con la cena.

Al término, la muerte decide ir a verlo, pero cuando ve entrar a la muerte en su casa, se arrepiente al instante de haberla llamado lleno de miedo.

Al término, la muerte decide ir a verlo, pero cuando ve entrar a la muerte en su casa, se arrepiente al instante de haberla llamado lleno de miedo.

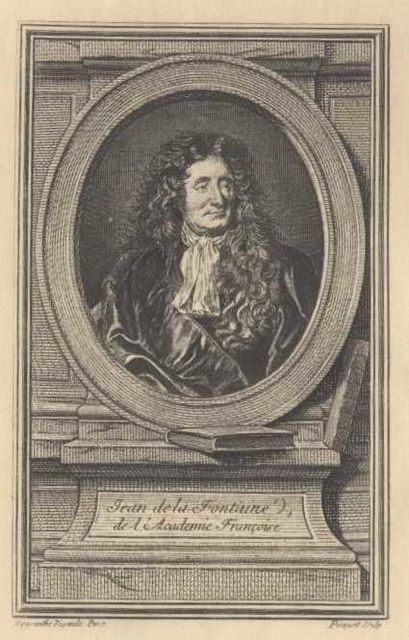

400 years ago, the remarkable French poet, writer and playwright Jean de La Fontaine, known to us today primarily as a fabulist, predecessor and teacher of Ivan Krylov, was born. But was this man famous only for fables? And do we understand his works correctly today, most of which, by the way, have not yet been translated into Russian? Philologist Natalya Pakhsaryan tells more about him and his creative path at the request of Gorky.

There are few readers in the world who would not know the name of Lafontaine and who have not preserved in their memory at least a few lines from his fables – in the original or in translations. Winged expressions from La Fontaine’s works are widely used both in speech and in writing. At the same time, there is no less popular poetic genre today than a fable, and it is unlikely that anyone, after mastering the school curriculum, begins to re-read such works. However, Jean de La Fontaine (1621-1695) is worthy of us remembering his jubilee, if only because his work did not at all boil down to composing fables. This one of the greatest French poets was also a lyricist, storyteller, short story writer, playwright, librettist, novelist, and translator. But the general readership knows almost nothing about the diversity of his work today.

This is partly due to the fact that not all of La Fontaine’s writings were as popular as his fables. His first work, a verse adaptation of Terence’s comedy The Eunuch, published anonymously, was not successful and is regarded by most critics as unsuccessful. La Fontaine had yet to plunge into the literary environment and realize his own writing talent. Born into a provincial family of a warden of waters and forests, he first studied Latin at a college in Château-Thierry, at the age of twenty he felt a vocation for theology and entered one of the seminaries in Paris, but as a reader he preferred secular rather than religious writings. While still in college, having heard the poems of Malherbe, which were read by one of the officers in the garrison of Château-Thierry, he began to memorize them and at night, going into the forest, recited them. However, his own poetic talent was not immediately revealed to him. At first, Lafontaine decided to study law and even received a lawyer’s degree in order to take up the same position of caretaker of waters and forests at the age of thirty-one that his father held. But he performed his duties so carelessly that Colbert was forced to sternly reprimand the negligent caretaker and begin an investigation into the damage caused to the forests.

La Fontaine had yet to plunge into the literary environment and realize his own writing talent. Born into a provincial family of a warden of waters and forests, he first studied Latin at a college in Château-Thierry, at the age of twenty he felt a vocation for theology and entered one of the seminaries in Paris, but as a reader he preferred secular rather than religious writings. While still in college, having heard the poems of Malherbe, which were read by one of the officers in the garrison of Château-Thierry, he began to memorize them and at night, going into the forest, recited them. However, his own poetic talent was not immediately revealed to him. At first, Lafontaine decided to study law and even received a lawyer’s degree in order to take up the same position of caretaker of waters and forests at the age of thirty-one that his father held. But he performed his duties so carelessly that Colbert was forced to sternly reprimand the negligent caretaker and begin an investigation into the damage caused to the forests. Finally, La Fontaine resigned from his burdensome position. Tallemand de Reo, a collector of anecdotes about contemporaries, called Lafontaine “a big eccentric” who completely forgot about his duties both in work and in family life, “sometimes considering himself unmarried for three weeks in a row.” Literature became the real and great love of the future fabulist, although he himself was not inclined to express this love sublimely pathetically. Having placed a comic epitaph to himself in the second volume of Fairy Tales and Novels in Poetry, La Fontaine claimed in it that his life was divided into two parts: “one for sleep, the other for idleness.” Such an ironic attitude towards oneself, I think, is a sign not only of wit, but also of the true mind of the poet. Calling himself a “loafer” Lafontaine managed to write an extremely large amount.

Finally, La Fontaine resigned from his burdensome position. Tallemand de Reo, a collector of anecdotes about contemporaries, called Lafontaine “a big eccentric” who completely forgot about his duties both in work and in family life, “sometimes considering himself unmarried for three weeks in a row.” Literature became the real and great love of the future fabulist, although he himself was not inclined to express this love sublimely pathetically. Having placed a comic epitaph to himself in the second volume of Fairy Tales and Novels in Poetry, La Fontaine claimed in it that his life was divided into two parts: “one for sleep, the other for idleness.” Such an ironic attitude towards oneself, I think, is a sign not only of wit, but also of the true mind of the poet. Calling himself a “loafer” Lafontaine managed to write an extremely large amount.

“Adonis” by La Fontaine. A page from the French edition of 1701

At the age of 35, having become close to the circle of the Knights of the Round Table, which included the writers Maukroi, Pelisson, Furetière and Tallemand de Reo, Lafontaine was finally carried away by the heroic odes of Malherbe and the elegant secular poetry of Voiture, the writings of Rabelais, Clement Marot, Boccaccio, Machiavelli, Ariosto, not to mention the ancient authors: Homer and Plato, Quintilian and Plutarch, Virgil, Horace and Ovid gave food to his imagination. He began to compose rondos, madrigals, ballads in the spirit of Marot, gained a reputation as a pleasant secular poet, which allowed him, through the mediation of his wife’s uncle, Mr. Jeannard, to receive the patronage of Nicolas Fouquet, Minister of Finance under Louis XIV. Surrounded by Fouquet, the future fabulist met other favorites of the minister – Madame de Sevigne, Molière and Racine. After Lafontaine wrote the poem “Adonis”, in which experts find a stylization-imitation of the poetry of the Italian Baroque poet Giovanni Marino, Fouquet awarded him a generous pension. In the same year, the poet, commissioned by his patron, began to write the allegorical poem “Dream in Vaud” with the aim of glorifying partly realized, partly still imaginary beauties of the Vaux-le-Comte palace and park ensemble under construction. It was not possible to complete the poem – in 1661, Fouquet was arrested for financial abuse, and the faithful La Fontaine, sincerely attached to the disgraced minister, switched first to the mournful “Elegy to the Nymphs of Vaud”, and then to “Ode to the King in Defense of Monsieur Fouquet” calling on the autocrat for mercy.

He began to compose rondos, madrigals, ballads in the spirit of Marot, gained a reputation as a pleasant secular poet, which allowed him, through the mediation of his wife’s uncle, Mr. Jeannard, to receive the patronage of Nicolas Fouquet, Minister of Finance under Louis XIV. Surrounded by Fouquet, the future fabulist met other favorites of the minister – Madame de Sevigne, Molière and Racine. After Lafontaine wrote the poem “Adonis”, in which experts find a stylization-imitation of the poetry of the Italian Baroque poet Giovanni Marino, Fouquet awarded him a generous pension. In the same year, the poet, commissioned by his patron, began to write the allegorical poem “Dream in Vaud” with the aim of glorifying partly realized, partly still imaginary beauties of the Vaux-le-Comte palace and park ensemble under construction. It was not possible to complete the poem – in 1661, Fouquet was arrested for financial abuse, and the faithful La Fontaine, sincerely attached to the disgraced minister, switched first to the mournful “Elegy to the Nymphs of Vaud”, and then to “Ode to the King in Defense of Monsieur Fouquet” calling on the autocrat for mercy. Having angered Louis XIV and Colbert, who replaced Fouquet, with such an attitude towards the minister who had fallen into disfavor and was forced to go after Jeannard into exile in Limoges, Lafontaine paid tribute to the epistolary genre, composing Letters from Limoges addressed to his wife (1663), four of which will be published only in 1729-m, and all six – only in 1820.

Having angered Louis XIV and Colbert, who replaced Fouquet, with such an attitude towards the minister who had fallen into disfavor and was forced to go after Jeannard into exile in Limoges, Lafontaine paid tribute to the epistolary genre, composing Letters from Limoges addressed to his wife (1663), four of which will be published only in 1729-m, and all six – only in 1820.

At the same time, La Fontaine’s literary talent was only gaining strength: having settled in the Luxembourg Palace after he was patronized by the Duchess of Bouillon and Orleans, he turned to writing fairy tales and short stories in verse , the first collection of which was published in 1665 and brought great success to the author. Drawing plots from the collection One Hundred New Novels, the works of Boccaccio and Ariosto, La Fontaine simultaneously demonstrated his attachment to the Renaissance tradition and mastery of the style of contemporary literature. In vain one of the critics of the XIX century. considered La Fontaine almost a Renaissance writer, “accidentally abandoned in the 17th century”: the poet consciously transforms well-known plots, changes the nature of Renaissance comedy, making his tales laconic frivolous-ironic stories in which there is an equilibrium ratio of simplicity and elegance, delicacy and gaiety, measure and deliberate negligence. It is no coincidence that a dispute arose among contemporaries about the merits and demerits of the Giocondo tale, which rewrites an episode from Ariosto’s poem “Furious Roland”: comparing Lafontaine’s text with a previously published translation of a certain Bouillon, other readers found that Bouillon was more faithful to the Italian original. However, such an authoritative arbiter as Nicolas Boileau spoke out in defense of the tale, since he considered La Fontaine’s work to be more decorous and respecting the principle of plausibility. The poetics of classicism became the basis of the principle of free circulation with the original of the plot, defended by La Fontaine, but not only it. His desire to “attract the reader, amuse him, keep his attention, please him, finally,” as he himself admitted in the preface to the second collection of Fairy Tales and Short Stories, gave rise to that aesthetic compromise, which was more pronounced in subsequent collections of verse fairy tales and short stories and, according to the correct remark of the modern researcher Galina Ermolenko, he demonstrated the emergence of rococo aesthetics in these works.

It is no coincidence that a dispute arose among contemporaries about the merits and demerits of the Giocondo tale, which rewrites an episode from Ariosto’s poem “Furious Roland”: comparing Lafontaine’s text with a previously published translation of a certain Bouillon, other readers found that Bouillon was more faithful to the Italian original. However, such an authoritative arbiter as Nicolas Boileau spoke out in defense of the tale, since he considered La Fontaine’s work to be more decorous and respecting the principle of plausibility. The poetics of classicism became the basis of the principle of free circulation with the original of the plot, defended by La Fontaine, but not only it. His desire to “attract the reader, amuse him, keep his attention, please him, finally,” as he himself admitted in the preface to the second collection of Fairy Tales and Short Stories, gave rise to that aesthetic compromise, which was more pronounced in subsequent collections of verse fairy tales and short stories and, according to the correct remark of the modern researcher Galina Ermolenko, he demonstrated the emergence of rococo aesthetics in these works.

Constantly referring to various ancient and renaissance sources, in fact, creating his works almost always on the basis of borrowed plots, Lafontaine nevertheless transforms them so individually that he turns out to be a full-fledged author of his stories. Thus, the small prosimetric novel The Love of Psyche and Cupid, which appeared in 1669, whose plot outline was taken from Apuleius’ Golden Ass, became an excellent example of those “inventions” that allowed the author to create a text that combines the poetics of classicism with the gallant poetics of the secular Literature – a harbinger of Rococo. The work becomes both a reworking of a well-known plot and a kind of aesthetic manifesto of the author: framed by a love story of mythological characters, it tells about the trip of four literary friends – Polyphilus, Acanthus, Arista and Gelast – from Paris to Versailles, as well as their conversations. Each of the interlocutors, sharing a common dislike for the “pedantic judgments” of supporters of academicism in literature, gravitates towards a certain style and not only listens to Poliphilus’ story about Cupid and Psyche, but also expresses his own opinions. And in the preface, Lafontaine talks about the search for a new style, about his desire to be both playful and natural, gallant and playful. It is no coincidence that already in the second half of the 18th century. this work attracted the attention of Ippolit Bogdanovich, who created on its basis the ironic rocaille poem “Darling”.

And in the preface, Lafontaine talks about the search for a new style, about his desire to be both playful and natural, gallant and playful. It is no coincidence that already in the second half of the 18th century. this work attracted the attention of Ippolit Bogdanovich, who created on its basis the ironic rocaille poem “Darling”.

Portrait of La Fontaine, artist unknown. The inscription at the top: “Variety”

La Fontaine did not confine himself to one genre or even a kind of literature. It is curious that this “man with many faces” (in the words of Patrick Dandre) could almost simultaneously compose free-thinking frivolous erotic tales and religious poems: for example, he participates in the “Collection of Christian Poetry” prepared by the authors of Port-Royal, and three years later publishes Jansenist poem “Saint Malchus in Captivity”. Leaving no attempts to conquer the stage, he first composes the comedy “Klymene”, then the libretto of the opera “Daphne”, however, rejected by the composer Lully; nine years later, he writes the comedy “Date”, the text of which is now lost (which most likely indicates its failure with the public), then, on the basis of Scarron’s novel, together with the actor Chevilet de Chanmelet, creates a five-act play “Ragotin, or Comic Romance”, a little later – comedy “The Florentine”, followed by the play “The Magic Cup” on the plot of Ariosto, finally, in 1691 year creates a new operatic libretto for the readers’ favorite novel of the 17th century. – “Astrea” by Honore d’Urfe (music by Colasses). However, this opera was a failure. Although Dubos, an early 18th-century critic, claimed that La Fontaine’s comedies “went to the incessant whistle of the orchestra” (and the same fate awaited his operatic librettos), the author of the preface to the 1883 edition of Ragotin speaks of them quite differently – “free , joyful, inspired, really worthy of this genius of the great age. In any case, it is important to note that at least one of La Fontaine’s comedies, The Magic Cup, gained fame not only in France – its anonymous translation into Russian was published in 1788 by Nikolai Novikov. As for the operatic librettos, Lafontaine, in a letter to the musician Pierre de Nier, written three years after Lully’s rejection of Daphne, explained their failure by the fact that gentle pastoral motifs, the sounds of the flute, attracted him more than the loud heroic music of large orchestras. , popular in contemporary theater.

– “Astrea” by Honore d’Urfe (music by Colasses). However, this opera was a failure. Although Dubos, an early 18th-century critic, claimed that La Fontaine’s comedies “went to the incessant whistle of the orchestra” (and the same fate awaited his operatic librettos), the author of the preface to the 1883 edition of Ragotin speaks of them quite differently – “free , joyful, inspired, really worthy of this genius of the great age. In any case, it is important to note that at least one of La Fontaine’s comedies, The Magic Cup, gained fame not only in France – its anonymous translation into Russian was published in 1788 by Nikolai Novikov. As for the operatic librettos, Lafontaine, in a letter to the musician Pierre de Nier, written three years after Lully’s rejection of Daphne, explained their failure by the fact that gentle pastoral motifs, the sounds of the flute, attracted him more than the loud heroic music of large orchestras. , popular in contemporary theater.

The 1680s is a period of particularly active and varied work of the poet. Perhaps under the influence of his new patroness, Madame de La Sablière, who showed an interest in philosophy and the natural sciences, La Fontaine tries himself in another genre, composing the “Poem of the cinchona tree”. Between 1680 and 1685 sketches the tragedy “Achilles”, the manuscript of the first two acts of which he sends to his friend Maukroy for judgment. He wants to be admitted to the French Academy, but Louis XIV is in no hurry to give his consent, and therefore the writer multiplies the praises of the monarch and even promises not to write more free-thinking fairy tales. As you know, he did not keep his word, but in 1684 he nevertheless became a member of the Academy. As a speech of thanks at the acceptance ceremony, he pronounces a laudatory word written in verse to Madame de La Sablière. Serious about his duties as an academician, Lafontaine attends all meetings, actively takes part in the famous “dispute about the ancient and the new”, taking, contrary to his friendship with the “innovator” Charles Perrault, the side of the defenders of the “ancients”.

Perhaps under the influence of his new patroness, Madame de La Sablière, who showed an interest in philosophy and the natural sciences, La Fontaine tries himself in another genre, composing the “Poem of the cinchona tree”. Between 1680 and 1685 sketches the tragedy “Achilles”, the manuscript of the first two acts of which he sends to his friend Maukroy for judgment. He wants to be admitted to the French Academy, but Louis XIV is in no hurry to give his consent, and therefore the writer multiplies the praises of the monarch and even promises not to write more free-thinking fairy tales. As you know, he did not keep his word, but in 1684 he nevertheless became a member of the Academy. As a speech of thanks at the acceptance ceremony, he pronounces a laudatory word written in verse to Madame de La Sablière. Serious about his duties as an academician, Lafontaine attends all meetings, actively takes part in the famous “dispute about the ancient and the new”, taking, contrary to his friendship with the “innovator” Charles Perrault, the side of the defenders of the “ancients”.

Madame de La Sablière died in 1692, but Lafontaine found new patrons – the d’Hervar couple – and settled in their castle of Bois-le-Vicomte. At this time, he translated hymns, psalms, the Latin poem by the Italian Tommaso da Celano “Judgment Day” and, in addition, in September 1694 he published the final, XII book of fables. And in April 1695, Lafontaine, “this kindest, most sincere soul that I have ever known,” as his friend Maukroy writes in his memoirs, died.

Of course, the main thing in La Fontaine’s legacy is his fables. This ancient genre, which was originally not even classified as fiction, the writer transforms, creating perfect poetry, marked by impeccable taste, flexible intonation, combining unobtrusive didacticism and sanity with natural images and subtle verbal play. As one of the modern critics put it, “It’s a pity that the too schoolboy approach to Lafontaine’s fables leaves aside their true scale: they are, first of all, works of art, poetry.” La Fontaine’s contemporaries highly valued the “poetic truth” of his fables, it is no coincidence that the collections he published were perhaps the most successful editions of the entire “Great Century”, so full of literary achievements that gave rise to the classics of French literature – Corneille, Racine, Molière, La Rochefoucauld and Madame de Lafayette .

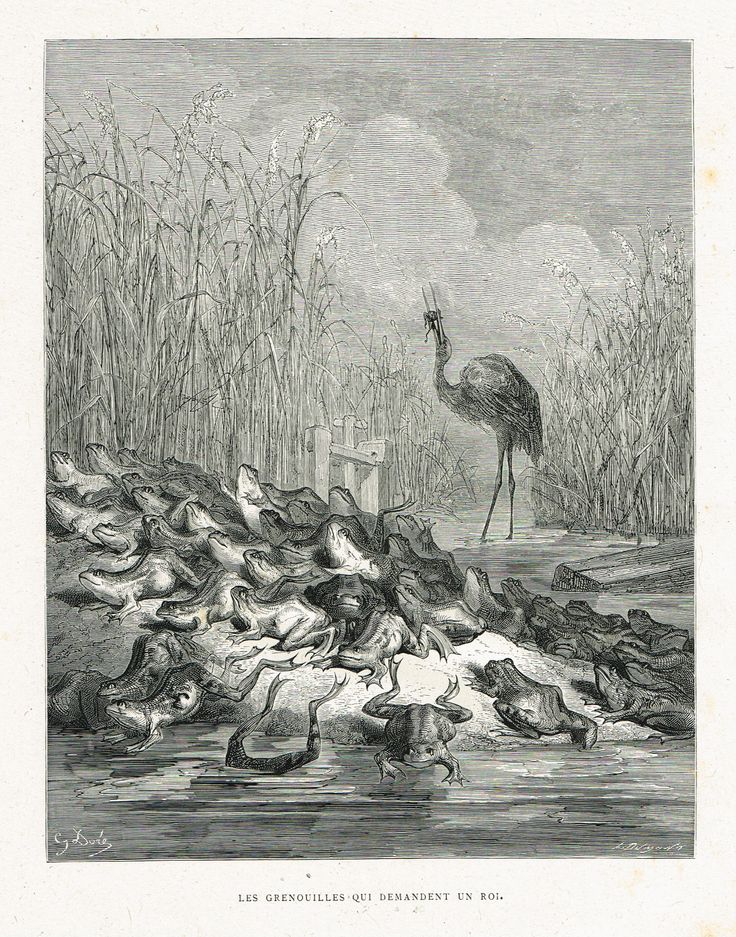

Pretitle of the first edition of the collection of La Fontaine’s fables, 1668

At the same time, La Fontaine the fabulist remains true to himself, not inventing plots, but borrowing them from various sources. The first collection of fables, published in 1668 and dedicated to the six-year-old Duke of Burgundy, the eldest son of Louis XIV, La Fontaine publishes under the title “Aesop’s Fables Transcribed into Poetry by Mr. La Fontaine”. It includes six books, including 124 fables. In total, the poet published twelve books, which included a total of 240 fables. Not a single plot in them was composed by Lafontaine himself, but not a single one went unnoticed due to the freshness, originality and genre and style innovation of the author. As he stated in his “Epistle to the Bishop of Soissons”, “there is nothing slavish in my imitation”, and this is an eminently fair assessment. “Using animals to teach people”, as has long been customary in the fable genre, La Fontaine essentially acts in it either as a lyricist, or as a satirist, sometimes with an ironic, sometimes with an elegiac intonation, blurring genre boundaries. Although the poet did not leave memoirs, did not write poetic confessions, Roger Duchen assures that “no one spoke so much about himself in the 17th century as Lafontaine” – including through the genre usually associated with allegorical teaching. Perhaps that is why he always turns out not to be a moralist, but a poet, although each of his fables explicitly or implicitly contains a moral lesson. It is no coincidence that critics are still arguing about how instructive La Fontaine’s fables are. Vasily Zhukovsky, for example, was sure that they had no morality at all, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau questioned their educational impact. A modern French researcher calls Lafontaine’s didacticism deceptive because of its duality and multiple meanings. But, perhaps, the point is not in the deceitfulness of the fabulist’s teachings, but in their tone, in the attitude of the author to the readers. As Hippolyte Taine rightly noted, Lafontaine, “the good fellow,” as many of his contemporaries called him, is never either selfish or harsh towards people, although he describes in his fables the whole of human nature, and not just its individual sides.

Although the poet did not leave memoirs, did not write poetic confessions, Roger Duchen assures that “no one spoke so much about himself in the 17th century as Lafontaine” – including through the genre usually associated with allegorical teaching. Perhaps that is why he always turns out not to be a moralist, but a poet, although each of his fables explicitly or implicitly contains a moral lesson. It is no coincidence that critics are still arguing about how instructive La Fontaine’s fables are. Vasily Zhukovsky, for example, was sure that they had no morality at all, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau questioned their educational impact. A modern French researcher calls Lafontaine’s didacticism deceptive because of its duality and multiple meanings. But, perhaps, the point is not in the deceitfulness of the fabulist’s teachings, but in their tone, in the attitude of the author to the readers. As Hippolyte Taine rightly noted, Lafontaine, “the good fellow,” as many of his contemporaries called him, is never either selfish or harsh towards people, although he describes in his fables the whole of human nature, and not just its individual sides. That is why the sharp rejection of La Fontaine by the romantic Lamartine (“La Fontaine’s Fables is a harsh, cold and selfish senile philosophy”) provoked a protest from the well-known critic Charles Sainte-Beuve, who, following Voltaire, saw in the fabulist the “French Homer”, whose “common sense, firmly merged with unique and pure talent” provides him with immortality. In the opinion of another critic of the Romantic era, Joubert, “there is in Lafontaine a fullness of poetry that is not to be found in any other French author.”

That is why the sharp rejection of La Fontaine by the romantic Lamartine (“La Fontaine’s Fables is a harsh, cold and selfish senile philosophy”) provoked a protest from the well-known critic Charles Sainte-Beuve, who, following Voltaire, saw in the fabulist the “French Homer”, whose “common sense, firmly merged with unique and pure talent” provides him with immortality. In the opinion of another critic of the Romantic era, Joubert, “there is in Lafontaine a fullness of poetry that is not to be found in any other French author.”

La Fontaine’s fable heritage played a special role in Russian literature. Translations of his fables appeared in Russia already in the 18th century, among the translators were Sumarokov and Dmitriev, Khemnitser and Batyushkov, Izmailov and Zhukovsky. Pushkin loved and knew the poems of “the careless lazy man, the simple-hearted sage, Vanyusha Lafontaine”. But first of all, it should be emphasized that without La Fontaine, our famous fabulist Ivan Krylov would not have been born, who began by imitating the French writer, widely using his experience, but in the end finding his own poetic voice. A lot of research has been devoted to comparing Krylov and Lafontaine, noting how the plot and structure of fables, their style and tone are transformed by the Russian author. The confrontation between La Fontaine’s classicism and Krylov’s realism invariably comes to the fore. Thus, Sergey Averintsev considers Lafontaine “the forerunner of the Enlightenment, forging the weapon of battles of this era – the poetics of rational clarity.” However, it is worth doubting whether the French writer is so clear and unambiguous even in his simplest judgments, whether he is so militant. The “enchanter” and “sage” La Fontaine is surprisingly many-sided, appearing in the eyes of biographers as a “genius of metamorphosis”, “a dreamer and a man of the world, a Parisian and a provincial, an erudite and a simpleton, a lover of pleasures and a sincere believer.” Just as diverse is his poetic heritage, which makes us wonder if we really know him and how deeply we understand him. Perhaps we have yet to read Lafontaine for real?

A lot of research has been devoted to comparing Krylov and Lafontaine, noting how the plot and structure of fables, their style and tone are transformed by the Russian author. The confrontation between La Fontaine’s classicism and Krylov’s realism invariably comes to the fore. Thus, Sergey Averintsev considers Lafontaine “the forerunner of the Enlightenment, forging the weapon of battles of this era – the poetics of rational clarity.” However, it is worth doubting whether the French writer is so clear and unambiguous even in his simplest judgments, whether he is so militant. The “enchanter” and “sage” La Fontaine is surprisingly many-sided, appearing in the eyes of biographers as a “genius of metamorphosis”, “a dreamer and a man of the world, a Parisian and a provincial, an erudite and a simpleton, a lover of pleasures and a sincere believer.” Just as diverse is his poetic heritage, which makes us wonder if we really know him and how deeply we understand him. Perhaps we have yet to read Lafontaine for real?

ID: 2013-02-27-T-2199

Thesis

Jean de Lafontaine – creator and reformer of the fable genre

Lunkevich D. O.

O.

Supervisor: Candidate of Philological Sciences, Associate Professor Polukhina O.N.

Saratov State Medical University named after Razumovsky Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation

Department of Russian and Classical Philology

J. La Fontaine went down in history as a famous French fabulist of the 17th century. His works were remarkable for their amazing variety, rhythmic perfection, skillful use of archaisms, sober view of the world and vivid imagery. The poet often used personifications, while relying on national traditions. The significance of La Fontaine for the history and theory of literature lies in the fact that he created a new genre, borrowing an external plot from ancient authors.

In antiquity, the fable served as a model of worldly wisdom, a means of education and a form of satire. In the early stages of human civilization, animal tales were taken literally; the fable as a literary genre arose only when animals began to be seen as symbols of human virtues and vices.

In 1668, the first six books of fables appeared under the modest title: Aesop’s Fables, Transcribed to Verse by M. de La Fontaine. It was the first collection that included the famous, later arranged by I. A. Krylov “Crow and Fox” and “Dragonfly and Ant”. The second edition appeared in 1678, and the third, with the inclusion of the twelfth and last book, at the end of 1693 years. The first two books are didactic in nature; in the rest, Lafontaine becomes more and more free. Lafontaine teaches a sober view of life, the ability to use circumstances and people, and constantly draws the triumph of the clever and cunning over the simple and kind. The artistic significance of Lafontaine’s fables is also facilitated by the beauty of poetic introductions and digressions, his figurative language, the special art of conveying movements and feelings in rhythm, the amazing richness and variety of poetic form. La Fontaine’s fables are written in most cases in free verse.

Lafontaine’s attitude to “morality” deserves special attention, which is such a natural conclusion from the situation depicted that it is often put into the mouth of one of the characters.