5 minutos

En medio de la inmensidad de desafíos que nos presenta la adolescencia, uno muy importante es el de superar los miedos y convivir con ellos. Descubre aquí cuáles son los más frecuentes.

Revisado y aprobado por el psicólogo Bernardo Peña.

Escrito por Fernando Clementin

Última actualización: 06 enero, 2022

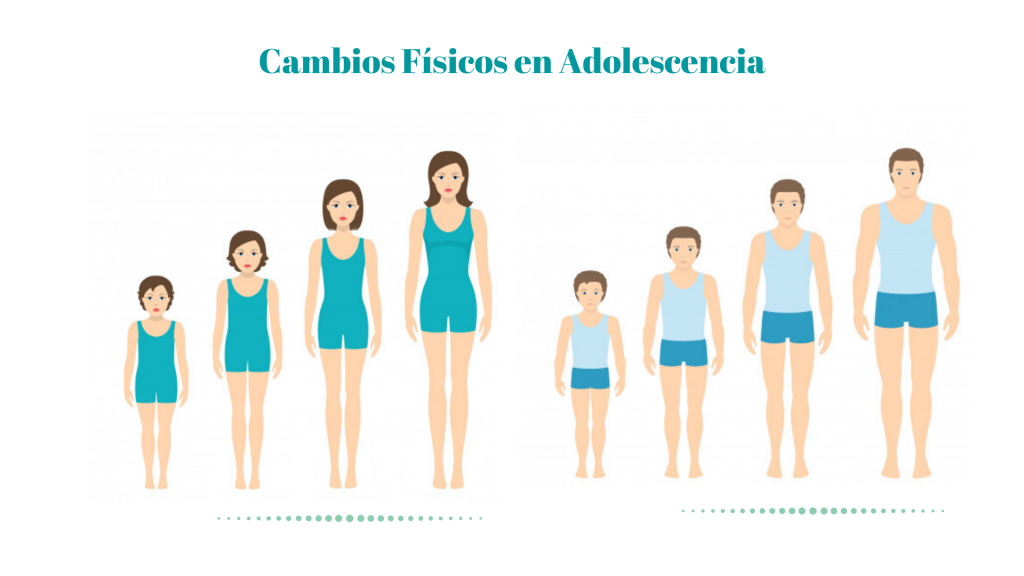

La adolescencia no es una etapa sencilla, más allá de las indiscutibles vivencias hermosas que nos ofrece. En ella se combinan grandes cambios físicos, hormonales, psicológicos y sociales. Por la suma de estos factores, los miedos en la adolescencia son algo común y que todos los jóvenes deben afrontar.

Entre los 12 años y los veintitantos —este límite se ha ido corriendo en los últimos años—, la adolescencia plantea grandes retos a la mentalidad de los exniños. Deben adaptarse, en primer lugar, a las alteraciones en su cuerpo y a los cambios psicológicos que estas producen.

Por otra parte, inician un proceso de independencia parcial de sus padres, por lo que muchas veces manifiestan públicamente rechazo hacia ellos. En sentido opuesto está su anhelo por incorporarse a un grupo de pares. Ligado a esto, vienen los problemas de identidad y miedo al rechazo.

Sin duda, es un combo casi incontrolable de sensaciones a las que, necesariamente, hay que hacer frente. ¿Cuáles son, entonces, los miedos en la adolescencia? ¿En qué podemos ayudar a nuestros hijos?

En realidad, los los miedos en la adolescencia no difieren demasiado de los de la adultez. Se experimenta temor al rechazo, al fracaso, a la soledad, al amor, entre otros. Lo que sí es diferente es el contexto en el que estas emociones se dan.

Durante la juventud, uno tiene la vida por delante. Esto ofrece muchas posibilidades y esperanzas, pero también una carga muy grande de incertidumbre.

En cambio, al crecer, algunas de estas cuestiones se van saldando. Por lo tanto, la estabilidad emocional aumenta y el cerebro se puede enfocar en el siguiente objetivo.

Por lo tanto, la estabilidad emocional aumenta y el cerebro se puede enfocar en el siguiente objetivo.

Una vez comprendida esta diferencia, podremos entender por qué la adolescencia es un periodo de transición, dudas y cuestionamientos a todos y a todo. Por eso se despiertan los siguientes miedos en la adolescencia.

Este surge, en gran medida, dada la preocupación constante de los padres por alejar a sus hijos de cualquier situación poco placentera. De este modo, viven en un permanente estado de comodidad y satisfacción, pero cuando llega un sacudón, las consecuencias son aún peores.

Desarrollar tolerancia a la frustración y, sobre todo, la capacidad de sobreponerse a la adversidad, es clave para toda persona. De no ser así, todos los planos de su vida se verán perjudicados: el laboral, sexual, familiar y social, entre otros.

Además es importante saber que no están obligados a cumplir las expectativas de nadie. Su única medida deberían ser ellos mismos: el objetivo es ser la mejor versión de uno.

Su única medida deberían ser ellos mismos: el objetivo es ser la mejor versión de uno.

A medida que el joven se va incorporando a la sociedad, notará todas las expectativas que hay posadas sobre él. Es frecuente que esto lo pueda atormentar. Un joven de 16 años, próximo a terminar el bachillerato, se encuentra frente a las siguientes decisiones:

Estos son solo algunos, ya que puede haber otras interrogantes a corto o largo plazo que también invaden su mente. Estos miedos en la adolescencia pueden causar ansiedad, inseguridad y falta de autoestima. Es necesario mucho apoyo para que el chico tenga a quien confiar sus inquietudes y una voz que transmite serenidad.

“Desarrollar tolerancia a la frustración y, sobre todo, la capacidad de sobreponerse a la adversidad, es una cualidad fundamental para toda persona”.

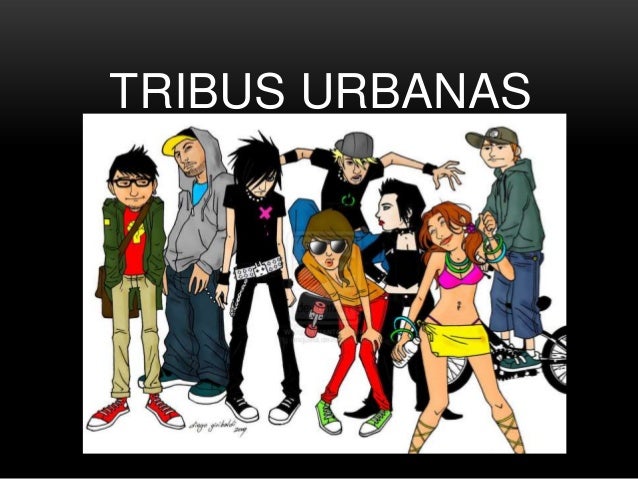

Los adolescentes aún no tienen totalmente definida su identidad. Por lo tanto, la van formando mediante la interacción con otros pares o grupos de personas.

Sin embargo, cuando no se logra esta interacción, el adolescente puede sufrir temores muy profundos. Esto los puede impulsar a cambios precipitados, cuestionamientos sobre sus valores e incluso la adopción de hábitos nocivos, solo por el hecho de ‘caer bien’.

El rechazo no es exclusivo del ámbito amoroso. También puede darse entre amigos, compañeros estudiantes o incluso por parte de adultos.

En este último caso, es habitual la preocupación excesiva por ser incluido en un equipo deportivo o en algún otro grupo selecto de estas características.

Así como en el camino de la adolescencia se van sumando muchas personas que a la larga se vuelven irreemplazables, también pasa lo contrario. Otros quedan relegados o directamente excluidos de nuestras vidas.

Otros quedan relegados o directamente excluidos de nuestras vidas.

Amigos de la infancia, familiares o incluso mascotas, sea por causas sentimentales o por pérdidas físicas, pueden abandonar nuestra cotidianidad. Estos cambios, sobre todo cuando son nuevas experiencias en la vida de un joven, pueden ser durísimos y generan mucho miedo.

Una vez más, y como a lo largo de todo este periodo, es fundamental el apoyo y la guía de personas experimentadas. Los padres, los abuelos y los hermanos mayores pueden ayudar a sobrellevar situaciones difíciles de manejar por su cuenta. Sobre todo las relativas a las pérdidas.

Debemos ratificar que los miedos en la adolescencia son normales y que estos promueven el desarrollo de una mentalidad sana y resiliente.

Si bien es importante ayudarlos, tampoco hay que resolverles todo. Cada persona debe hacer frente a las batallas personales para progresar y ser mejor día a día.

El miedo es un sentimiento normal y necesario en el desarrollo evolutivo. Su función es la de dar seguridad, ya que nos advierte de la presencia de un peligro y permite evaluar la capacidad que uno tiene para afrontar las amenazas y poder protegerse ante posibles riesgos. ¿Cuáles son los miedos más comunes de los jóvenes de hoy? Te contamos cuáles son los miedos más comunes en la adolescencia.

Su función es la de dar seguridad, ya que nos advierte de la presencia de un peligro y permite evaluar la capacidad que uno tiene para afrontar las amenazas y poder protegerse ante posibles riesgos. ¿Cuáles son los miedos más comunes de los jóvenes de hoy? Te contamos cuáles son los miedos más comunes en la adolescencia.

El miedo es una emoción universal presente en todas las culturas que aparece desde los 6 meses y que va evolucionando. Es decir, a medida que el niño pasa por las diferentes etapas del desarrollo los miedos van cambiando o desapareciendo gradualmente a medida que el niño experimenta la seguridad en sí mismo y en el entorno. También se manifiestan en la etapa adolescente.

La adolescencia es considerada una etapa de transición desde el estatus infantil al estatus de adulto. De este modo, se puede decir que los miedos que se tienen en la adolescencia pueden provenir de varios frentes:

– Los que se arrastran de la etapa anterior (la preadolescencia). Para el joven adolescente sigue teniendo importancia todo lo relacionado con no ser aceptado por los demás (que cobra fuerza en este periodo) y tiene miedo al fracaso escolar.

Para el joven adolescente sigue teniendo importancia todo lo relacionado con no ser aceptado por los demás (que cobra fuerza en este periodo) y tiene miedo al fracaso escolar.

– Los miedos de adulto. En las edades que comprenden la adolescencia, los jóvenes comienzan a experimentar con nuevos miedos que pueden etiquetarse como miedos adultos. Estos son, por ejemplo: el amor, el futuro que vendrá, estar solos, etc.

La adolescencia, por tanto, no se considera una etapa fácil. Es un periodo de grandes cambios físicos y psicológicos que no permiten alcanzar el equilibrio emocional necesario para afrontar todos esos miedos.

De este modo, la carencia de estabilidad emocional en el adolescente es lo que le diferencia de un adulto a la hora de encarar los miedos.

Existen muchos tipos de miedo que pueden afectar en mayor o menor medida al adolescente. Estos son los más comunes:

1. Miedo a NO ser aceptado

La adolescencia se caracteriza por ser una etapa en la que el joven busca respuestas que le ayuden a descubrirse a sí mismo. Es decir, está en la búsqueda de una identidad que le diferencie de sus padres y le ayude a interactuar con sus iguales.

Es decir, está en la búsqueda de una identidad que le diferencie de sus padres y le ayude a interactuar con sus iguales.

El joven experimenta una preocupación excesiva por ser incluido en ese tipo de grupos formados por individuos de su edad. No obstante, si no lo logra, esto provocará temor y miedo. Algo muy común en este periodo.

2. Miedo al amor

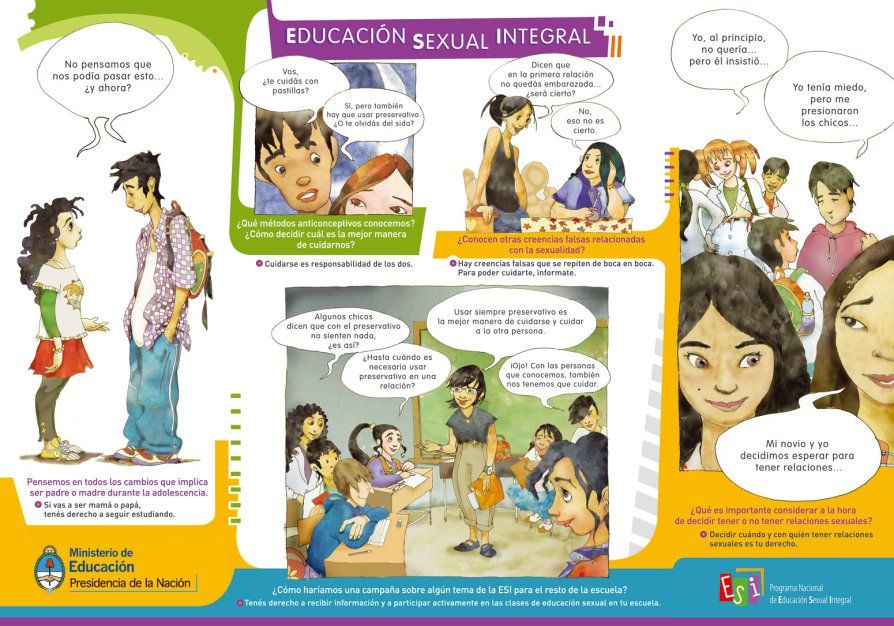

La adolescencia es la etapa en la que suele aparecer el amor. Una mezcla de emociones difícil de definir y más cuando en este periodo los jóvenes experimentan grandes desequilibrios emocionales.

Si a esto le sumamos la continua búsqueda de identidad, la inseguridad y la inexperiencia características de esta etapa, encontramos que los jóvenes son muy vulnerables a esta emoción compleja y, por tanto, estamos ante uno de los miedos más comunes de este periodo del desarrollo.

3. Miedo a lo que está por venir

El fin que busca el adolescente es la integración en la sociedad. A medida que lo consigue se da cuenta que tiene que ‘cumplir’ unas expectativas que los adultos de su entorno han depositado en él para alcanzar unas metas en el futuro.

A medida que lo consigue se da cuenta que tiene que ‘cumplir’ unas expectativas que los adultos de su entorno han depositado en él para alcanzar unas metas en el futuro.

Las inseguridades que caracterizan esta etapa hacen que el joven se pregunte si puede conseguirlo. Por eso, el miedo a lo que vendrá en el futuro y si será capaz de afrontarlo cumpliendo las expectativas le infunden miedo.

Te damos todos estos consejos para ayudar a tu hijo adolescente a superar sus miedos:

– Escuchar lo que tiene que decir

Es fundamental permitir que los jóvenes expresen sin miedo sus sentimientos y emociones para que sientan el apoyo de los adultos de su entorno ante cualquier miedo e inseguridad.

– Estar a su lado

La adolescencia es una etapa en la que los jóvenes carecen de las habilidades necesarias para enfrentarse a situaciones que le s producen miedo y ansiedad. Por eso, será necesario que los adultos les acompañen para ser su apoyo.

– Dialogar

En esta etapa que nos ocupa a los jóvenes les cuesta hablar de sus sentimientos y emociones, por lo que será necesario crear un clima positivo para tratar los miedos que padezcan de manera natural.

Puedes leer más artículos similares a Los miedos más comunes en la adolescencia, en la categoría de Miedos en Guiainfantil.com.

↓

Josef Matthias Hauer

History does not consist only of frontiers, it is not a single, monolithic stream sweeping away everything in its path, a single channel. In addition to the main rhythms and motifs that give it integrity, it is woven from a variety of secondary themes, it has quiet backwaters. What we see at a distance, as a single, uniform, progressive movement, consists of fluctuations and eddies. In addition to the main names and phenomena that form the canon, there are many interesting, not so noticeable figures who, nevertheless, have contributed to the emerging historical landscapes; history is not only a delineated profile, but also many small touches that give flesh and density to the silhouettes drawn by historical time.

The names of Schoenberg, Webern, Berg as the founders of serial music are widely known, but they were not the only ones who tried to create a theoretical system that would become the basis of a new language of music in conditions of liberation from the fetters of tonality. Another such theorist and composer, whose work in historical perspective turned out to be not as significant as the achievements of Schoenberg, was the Austrian composer Josef Hauer.

In the history of music, Josef Hauer is best known as Schoenberg’s unsuccessful rival for the right to be called the father of the twelve-tone system. A few years before Schoenberg, namely at 19In the year 19, Hauer discovered the laws of twelve-tone composition and presented to the public in his verbose and numerous treatises this discovery: the doctrine of tropes or constellations. The material for constructing the melodic-harmonic basis of a piece in the Hauer system is combinations of 44 twelve-sound trope complexes or constellations (constellations). Unlike the Schoenberg series, the order of the sounds does not matter, the set of intervals presented in the path is important.

Unlike the Schoenberg series, the order of the sounds does not matter, the set of intervals presented in the path is important.

No one disputes Josef Hauer’s theoretical achievements, but usually one speaks of his music as something pale, faded, secondary, as a simple interlinear commentary on his theoretical thought. This seems unfair, since Hauer drew radical conclusions from the idea of \u200b\u200bthe equality of twelve tones – in this his music is similar to the music of Anton Webern. With such radicality and extreme originality of coloring, unlike the works of Schoenberg and the new Viennese school, it is, at least, interesting and unusual.

The beginning of Hauer’s musical path, like that of Schoenberg, was amateurish. Hauer was born in 1883 in the small provincial town of Wiener Neustadt, 50 kilometers from Vienna. There were no professional musicians in his family. He did not receive a systematic musical education. At the age of five, he begged his father to teach him to play the zither, then he learned to play the cello, independently studied H. Bellerman’s counterpoint textbook (the same one that Schoenberg himself studied and taught), trained by ear recording preludes and fugues from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. During these years, Hauer still does not think of music as his main business, he graduates from a pedagogical school, then at 1902 – 1914 teaches in general educational institutions. In parallel, with more and more interest and awareness, he discovers the world of composing music; at the age of 28, he realized himself as a composer.

Bellerman’s counterpoint textbook (the same one that Schoenberg himself studied and taught), trained by ear recording preludes and fugues from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. During these years, Hauer still does not think of music as his main business, he graduates from a pedagogical school, then at 1902 – 1914 teaches in general educational institutions. In parallel, with more and more interest and awareness, he discovers the world of composing music; at the age of 28, he realized himself as a composer.

Hauer writes in his treatise Sowing and Reaping:

“At 28 I can celebrate my spiritual rebirth. Before that, the arable land of my life lay uncultivated. In my youth, I did not even suspect that everything in me was tuned to music. But it is so. I once played music that only existed in dreams. All this happened in a small town, far from innovations, without an impulse from outside.”

Hauer takes his new career very seriously – he sells the cello, refuses a flattering offer to join the Vienna Philharmonic and devotes himself to writing. From the very beginning of his creative path, he is aware of himself as a composer who deliberately abandons tradition. Hauer wrote: “Everything that was handed down to me by tradition is no longer needed.” This focus on composing groundbreaking music “previously only dreamed of” will become the living nerve that will inspire his work throughout his life.

From the very beginning of his creative path, he is aware of himself as a composer who deliberately abandons tradition. Hauer wrote: “Everything that was handed down to me by tradition is no longer needed.” This focus on composing groundbreaking music “previously only dreamed of” will become the living nerve that will inspire his work throughout his life.

↓

At this time, in 1911-1913, Hauer wrote his first two opuses – piano symphonies, which, like many of his piano compositions, received the name “Nomos”. These works are symphonies with a certain degree of conventionality, for example, his first “Nomos” consists of seven parts, built in accordance with the principles of rhetorical contrast, which makes it related to the symphony, a genre that is precisely characterized by a contrasting musical narrative. These pieces, despite the fact that they are linear, flat and somewhat primitive experiments in the spirit of late romanticism, are nevertheless in tune with the great revolution and storm that the new music is making in the person of Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Bartok. However, these are still very simple experiments, experiments of the musical marginal; by this time, Stravinsky had already written The Rite of Spring, Schoenberg – Pierrot Lunar, Bartok – his scandalous and famous “Barbarian Allegro”.

However, these are still very simple experiments, experiments of the musical marginal; by this time, Stravinsky had already written The Rite of Spring, Schoenberg – Pierrot Lunar, Bartok – his scandalous and famous “Barbarian Allegro”.

The musical world seethes, contradictions collide in it, hitherto unshakable rules are overturned – Hauer is still aloof from these “storm and stress”. Through acquaintances, Hauer’s compositions come to the attention of professional musicians: in 1913, Rudolf Reti, one of the future founders of the International Society for New Music, premieres his first two nomos symphonies. The first premiere is a success, the second composition is a failure, but a start has been made. In the same 1913, Hauer tries to make contacts with Schoenberg and his school, but the latter does not feel like communicating with an amateur unknown to him. At this time, in his hometown, an intellectual circle begins to take shape around Hauer, he acquires a certain influence: he has his own table in a cafe, around which poets, artists, musicians gather; he is helped to write theoretical treatises by his friend, the religious philosopher Ferdinand Ebner, the author of the famous book The Word and Spiritual Realities. It is under the influence of Abner that Hauer develops an idea of the ideological background of 12-tone music – Hauer perceives the idea that art should serve as an expression of “absolute” and “impersonal”, “impersonal” realities, that it should be free from a sensual principle, from everything human, everyday, concrete. Music thus turns out to be the expression of a cosmic, superhuman law.

It is under the influence of Abner that Hauer develops an idea of the ideological background of 12-tone music – Hauer perceives the idea that art should serve as an expression of “absolute” and “impersonal”, “impersonal” realities, that it should be free from a sensual principle, from everything human, everyday, concrete. Music thus turns out to be the expression of a cosmic, superhuman law.

“If we seriously want to think about what it means to be human, then we must recognize that to be human means to realize that human existence implies the requirement to lead a spiritual existence, the requirement to strive for a higher being, for agreement with the divine principle,” writes Ferdinand Ebner in his diaries.

Thus, both art and music turn out to be a way to lead a spiritual existence, ways to build a bridge between the material, mundane, mundane and the divine, impersonal. The spiritual in man, according to Abner, is something as real as the objects of the physical world; however, the spirit in man sleeps and dreams, dreams of the world as an internally harmonious all-encompassing Cosmos. The life of the spirit and the creative life converge when creativity is directed to impersonal, objective spiritual realities, when creativity turns out to be a way to awaken a dormant spirit; it was this idea that Hauer learned well from his friend. Therefore, the composer’s music tends to be detached, it is calm, static, not aimed at expressing emotions, avoiding any expressive gestures.

The life of the spirit and the creative life converge when creativity is directed to impersonal, objective spiritual realities, when creativity turns out to be a way to awaken a dormant spirit; it was this idea that Hauer learned well from his friend. Therefore, the composer’s music tends to be detached, it is calm, static, not aimed at expressing emotions, avoiding any expressive gestures.

In 1919, already after the war, which he, thanks to his calligraphic handwriting, spent as a clerk in Vienna, Hauer retires due to nervous exhaustion; at this time, all his thoughts already completely belong to music, he is unable to teach, maintain discipline in the class, and fulfill the duties of a teacher. This year is a milestone, the most important in the composer’s biography. Hauer hooks up with wealthy and influential patrons who give premieres of his music; among them are the architect Adolf Loos and the writer Hermann Bahr. He is supported by the Kehert family of patrons. The composer becomes a frequent visitor to the famous salon of Alma Mahler. In the same year, the most significant creative revolution in the fate of Hauer takes place, which sums up all his past work – from writing in the spirit of a peculiar, rough, linear romanticism, he finally moves on to atonal music and the idea of equality of twelve tones.

In the same year, the most significant creative revolution in the fate of Hauer takes place, which sums up all his past work – from writing in the spirit of a peculiar, rough, linear romanticism, he finally moves on to atonal music and the idea of equality of twelve tones.

↓

Illustration fragment from Hauer’s theoretical work on the relationship between color and tone, influenced by Johannes Itten.

In 1919, he wrote the vocal composition “Sunny Melos”, created in a new technique. The title of this play metaphorically describes the essence of Hauer’s discovery: the modal system is like a solar system with a tone-sun in the center and planets-overtones around. It would be stable if there were no other suns with their planets. In order to avoid a catastrophe, so that planets and stars do not collide, it is necessary to arrange the musical space so that each sun has enough space, it is necessary to allow the tones to make room and make them yield to each other. Then the planets-sounds, which find themselves in the field of attraction of several stars-reference tones at once, will be able to move along complex but free trajectories. At the same time, Hauer met the outstanding Swiss abstract artist Johannes Itten; Hauer wrote about their creative union as about the friendship of the ear and the eye, which creates the perception of the whole. This collaboration is reminiscent of another, more famous union: Schoenberg and Kandinsky. Itten suggests that Hauer move to the Bauhaus and found a school of atonal music there, but due to various circumstances, the composer remains in Vienna and there, in January 1920, announces the creation of the school. Hauer began to actively appear in print with articles, read reports on the principles of atonal music. These speeches are so exciting that the Schlesinger publishing house published the brochure “The Struggle Around Josef Matthias Hauer”, which collected critical responses to his ideas. Hauer publishes many musical treatises in which he verbosely, freely and extremely metaphorically expresses his own ideas: “On the essence of the musical”, “From melos to timpani”, “Twelve-tone technique.

At the same time, Hauer met the outstanding Swiss abstract artist Johannes Itten; Hauer wrote about their creative union as about the friendship of the ear and the eye, which creates the perception of the whole. This collaboration is reminiscent of another, more famous union: Schoenberg and Kandinsky. Itten suggests that Hauer move to the Bauhaus and found a school of atonal music there, but due to various circumstances, the composer remains in Vienna and there, in January 1920, announces the creation of the school. Hauer began to actively appear in print with articles, read reports on the principles of atonal music. These speeches are so exciting that the Schlesinger publishing house published the brochure “The Struggle Around Josef Matthias Hauer”, which collected critical responses to his ideas. Hauer publishes many musical treatises in which he verbosely, freely and extremely metaphorically expresses his own ideas: “On the essence of the musical”, “From melos to timpani”, “Twelve-tone technique. The doctrine of paths. These years are the peak of the popularity of Hauer and his music. His compositions are performed at the leading festivals of new music, in Vienna, in Salzburg – and everywhere they are met with success. “Perhaps later they will say: Schubert, Bruckner, Hauer!” – this is how critics speak about his works.

The doctrine of paths. These years are the peak of the popularity of Hauer and his music. His compositions are performed at the leading festivals of new music, in Vienna, in Salzburg – and everywhere they are met with success. “Perhaps later they will say: Schubert, Bruckner, Hauer!” – this is how critics speak about his works.

↓

What is the secret of the success of this music, which found its way to hearts more easily than the compositions of the Novovensk school? In its unpretentious simplicity, rhythmic monotony, the absence of sharp, expressive gestures, in islands of tonal stability, euphony, in avoiding tense dissonances; this music is described as sublime, quiet, calm, lyrical, subtle. But at the same time, there is something of spiritual kitsch, easily digestible spiritual semi-finished products in Hauer’s writings. It resembles popular prints on religious themes.

The popularity of Hauer and his attempts to try on the laurels of the father of the twelve-tone technique could not but disturb Schoenberg. He could no longer ignore his competitor; in correspondence with Hauer, he writes that “we both found the same diamond, you look at it from one side, I look at it from the opposite side.” However, this correspondence, dating back to 1923, did not lead to fruitful cooperation. Schoenberg included his pieces in the programs of the Society for Closed Musical Performances, and Hauer dedicated two collections of etudes for piano to Schoenberg 1922 years and the treatise “From Melos to Timpani”, but subsequently the relationship was destroyed by mutual ambition. Hauer’s desire to establish at any cost his superiority in the discovery of the twelve-tone technique led to hostility in relations between Hauer and Schoenberg.

He could no longer ignore his competitor; in correspondence with Hauer, he writes that “we both found the same diamond, you look at it from one side, I look at it from the opposite side.” However, this correspondence, dating back to 1923, did not lead to fruitful cooperation. Schoenberg included his pieces in the programs of the Society for Closed Musical Performances, and Hauer dedicated two collections of etudes for piano to Schoenberg 1922 years and the treatise “From Melos to Timpani”, but subsequently the relationship was destroyed by mutual ambition. Hauer’s desire to establish at any cost his superiority in the discovery of the twelve-tone technique led to hostility in relations between Hauer and Schoenberg.

↓

Fragment of a sketch of the Hauer string quartet, written in 1954 and dedicated to the Austrian conductor Hans Rosbaud.

At the end of the twenties, Hauer’s popularity gradually faded; this is due to the growing strength of the neoclassical movement, in which his music obviously did not fit, as well as the influence and popularity of the Schoenberg school, in the face of which Hauer feels vulnerable. These feelings are expressed in the seal with which Hauer signed his letters at that time: in the inscription on it, the composer calls himself “a spiritual creator and (despite many imitators) still the only connoisseur and master of twelve-tone music.” Gradually, Hauer’s music disappears from publishing catalogs, it becomes unprofitable to print it. However, the composer remains very productive – he writes numerous works for orchestra, for piano, for musical theater. From 19For 39 years and until his death in 1959, the last stage of Hauer’s work lasts. He spent the years of the Nazi occupation of Austria in Vienna, without showing himself in public. After 1939, he wrote, or rather, synthesized with the help of the algorithm he invented, pieces for piano and various ensembles, simple in texture and structure, under the general name “Twelve-tone game” (Zwölftonspiele). In total, using this method, he painted more than 1000 similar miniatures, many of which are lost. Hauer himself declared, refusing the name of a composer and musician and preferring the concept of “interpreter of melos”, so rich in semantic overtones, that he writes the same piece all the time in accordance with the laws of intuitive twelve-tone music, the music of the Absolute.

These feelings are expressed in the seal with which Hauer signed his letters at that time: in the inscription on it, the composer calls himself “a spiritual creator and (despite many imitators) still the only connoisseur and master of twelve-tone music.” Gradually, Hauer’s music disappears from publishing catalogs, it becomes unprofitable to print it. However, the composer remains very productive – he writes numerous works for orchestra, for piano, for musical theater. From 19For 39 years and until his death in 1959, the last stage of Hauer’s work lasts. He spent the years of the Nazi occupation of Austria in Vienna, without showing himself in public. After 1939, he wrote, or rather, synthesized with the help of the algorithm he invented, pieces for piano and various ensembles, simple in texture and structure, under the general name “Twelve-tone game” (Zwölftonspiele). In total, using this method, he painted more than 1000 similar miniatures, many of which are lost. Hauer himself declared, refusing the name of a composer and musician and preferring the concept of “interpreter of melos”, so rich in semantic overtones, that he writes the same piece all the time in accordance with the laws of intuitive twelve-tone music, the music of the Absolute.

Interest in Hauer’s work revived for some time after the war against the background of the fashion for dodecaphony; Hauer received several honorary awards and received attention from influential musicians; his music began to be performed again, albeit not with such success and not as massively as in the 1920s. Despite numerous connections with the musical avant-garde: his music, for example, was appreciated by such different avant-garde geniuses as John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen — Hauer remained an isolated, marginal figure in the history of music. Hauer’s defeat in the dispute with Schoenberg was almost inevitable. Partly the reason is the cohesion of the Novovensk school, Schoenberg’s emigration to the USA, where his concepts received fertile ground. But there are also internal, purely ideological reasons. Schoenberg’s atonal music, in accordance with the ideals of modernity and expressionism, is a subtle fixation of the extreme manifestations of the subject’s inner life; moreover, it is composer’s music, while Hauer distanced himself from all subjectivity and even the concept of authorship. In Hauer’s music, especially later, minimalist tendencies are strong – it is characterized by a simple, suggestive rhythm, it is meditative, it tries to erase the boundaries between Self and not-Self; its monotony and rhythmic uniformity are a consequence of the ideas of Hauer, who believed that complex and expressive rhythms destroy the unity of melos. In Hauer’s music, especially later, there is no tense drama of feelings, no intense ups and downs, sharp fluctuations and surges are not characteristic of her – her speech is hypnotic, self-absorbed. Hauer believed that music is not composed, it must be heard and interpreted; it already exists – eternal, beginningless, endless – and the musician’s job is only to manifest it in the form of a sequence of sounds, in the form of a play of tones. Unlike the New Viennese school, which affirmed new worlds, new subjectivity, Hauer insisted on music as a way to get rid of one’s own Self, to go beyond any sensual worlds, as a way of exaltation and self-exaltation; travel to the world of already existing, eternal, unchanging spiritual realities.

In Hauer’s music, especially later, minimalist tendencies are strong – it is characterized by a simple, suggestive rhythm, it is meditative, it tries to erase the boundaries between Self and not-Self; its monotony and rhythmic uniformity are a consequence of the ideas of Hauer, who believed that complex and expressive rhythms destroy the unity of melos. In Hauer’s music, especially later, there is no tense drama of feelings, no intense ups and downs, sharp fluctuations and surges are not characteristic of her – her speech is hypnotic, self-absorbed. Hauer believed that music is not composed, it must be heard and interpreted; it already exists – eternal, beginningless, endless – and the musician’s job is only to manifest it in the form of a sequence of sounds, in the form of a play of tones. Unlike the New Viennese school, which affirmed new worlds, new subjectivity, Hauer insisted on music as a way to get rid of one’s own Self, to go beyond any sensual worlds, as a way of exaltation and self-exaltation; travel to the world of already existing, eternal, unchanging spiritual realities.

Hauer’s position led to the fact that his music and theoretical views could not resonate with the avant-garde demand for ultra-modernity, for the relevance of music. Music that tries to express the timeless, rather than the modern, literally finds itself outside the coordinates of modernity, that is, in a marginal position. Unlike Hauer, Schoenberg and his school were able to create an expressive and innovative language that described all the abysses and aspirations of the new world; and with this, the New Viennese fell into tune, turned out to be in tune with the thinking of composers and connoisseurs of music, managed to create and satisfy a new aesthetic need. Where Hauer made complete, hermetic statements, there the New Viennese opened up new possibilities, new paths; where Hauer produced a product, the New Viennese created discourse. Hauer’s music, unlike the music of the New Viennese, could not serve as a foundation for a new language, a new common practice; due to its extreme individuality, it is a brilliant dead end – it is complete, it is difficult to imagine how it could be developed. Long before Philip Glass, Steven Reich, Terry Riley, Josef Hauer wrote extremely peculiar minimalist, sacred, self-centered music – atonal minimalism, in which feeling and reason, contemplation and emotion were united in an indissoluble unity. Hauer’s traits are guessed in the character of Hermann Hesse’s “Glass Game”, in the Basel player who discovered “the principles of a new language, the language of signs and formulas, where mathematics and music belonged to equal shares.”

Long before Philip Glass, Steven Reich, Terry Riley, Josef Hauer wrote extremely peculiar minimalist, sacred, self-centered music – atonal minimalism, in which feeling and reason, contemplation and emotion were united in an indissoluble unity. Hauer’s traits are guessed in the character of Hermann Hesse’s “Glass Game”, in the Basel player who discovered “the principles of a new language, the language of signs and formulas, where mathematics and music belonged to equal shares.”

Josef Hauer is a second-tier composer and theorist, but his music is important for understanding the richness and heterogeneity of the 20th century musical landscape. History consists not only of a uniform movement along the main line, it is woven from accidents, shreds and fragments, it is like a placer, rich embroidery, sparkling with a hundred shades. One of such bright secondary tones in the history of music of the 20th century is Josef Hauer and his compositions.

***

If you liked the article, you can visit my VK group, where I publish notes about classical and modern music, as well as my own author’s music: EllektraCyclone.

You can also listen to my music on BandCamp.

The peak incidence of poliomyelitis occurred in the middle of the twentieth century, when this disease became a national disaster in many countries. The invention of polio vaccines and the vaccination of the population have led to the fact that in many countries this disease has been virtually eliminated.

There are three types of polio virus – types I, II and III. Type I is the most common. This virus is very resistant to external influences: it remains in water for up to 100 days, in feces for up to 6 months, it calmly tolerates freezing and is not destroyed by digestive juices. But it quickly dies when boiled, dried and exposed to ultraviolet radiation.

The virus can be transmitted from a sick person to a healthy person by airborne droplets, but most often it is transmitted through dirty hands, toys, utensils and food. You can also get it through stool if you do not follow the hygiene requirements. The incubation period is 5-12 days. First, the virus enters the mouth, from there it travels through the mucous membrane of the respiratory tract or the gastrointestinal tract to the spinal cord or brain, in some cases causing damage to the central nervous system.

The incubation period is 5-12 days. First, the virus enters the mouth, from there it travels through the mucous membrane of the respiratory tract or the gastrointestinal tract to the spinal cord or brain, in some cases causing damage to the central nervous system.

Poliomyelitis may be asymptomatic and infection can only be detected through laboratory testing. In other cases, after the incubation period, symptoms of the disease appear. At first, they resemble the common cold: cough, runny nose, sore throat. Then the person feels nausea and tension in the muscles of the neck and head, vomiting begins.

In the paralytic form, the temperature rises sharply, the head starts to hurt, digestive disorders are observed, the voice sits down. Then relief comes for 2-4 days, after which the disease returns: fever, cramps, pain in the back and limbs do not give rest. After 3-5 days, paralysis sets in, which lasts from 2 days to 2 weeks. The most dangerous is paralysis of the neck and diaphragm, which can lead to respiratory failure and death. After the temperature drops, recovery begins. Moreover, a full recovery can take even several years. Complete recovery without consequences after this form of poliomyelitis occurs in 30% of cases, but more often a person remains paralyzed with muscle atrophy, and death occurs in 10% of cases.

After the temperature drops, recovery begins. Moreover, a full recovery can take even several years. Complete recovery without consequences after this form of poliomyelitis occurs in 30% of cases, but more often a person remains paralyzed with muscle atrophy, and death occurs in 10% of cases.

Only one thing is reassuring: the paralytic form of poliomyelitis is quite rare: approximately 1% of cases.

Children of the first 2-3 months of life, thanks to the immunity received from the mother through the placenta (if the mother was vaccinated against polio), almost do not get polio. After the illness, a strong immunity is developed.

Children under 7 years of age are most susceptible to infection with the polio virus.

The best prevention of polio is vaccination. According to the national vaccination schedule in Russia, children are vaccinated against polio for the first time at 3 months, then at 4.5 months, at 6 months, 18 months, 20 months and 14 years. After 14 years, subject to the vaccination schedule, revaccination is no longer required.

After 14 years, subject to the vaccination schedule, revaccination is no longer required.

Two types of vaccines are used – live (with weakened virus) and inactivated. Since January 1, 2008 in Russia, the first 2 vaccinations against polio are carried out with an inactivated vaccine. In this case, the following vaccines are used: Tetrakok 05, Oral polio vaccine 1,2,3 types, Imovax polio, Polio Sabin Vero, Pentaxim.

Oral polio vaccine and Polio Sabin Vero vaccine contain attenuated polio viruses. These vaccines come in drops that you put in your mouth. They contribute to the formation of local immunity in the intestine.

After vaccination with a live vaccine, it is recommended, if possible, to isolate the baby from contact with the outside world for 2-3 days. Within an hour after vaccination, the child should not be allowed to drink and eat.

Inactivated polio vaccine Imovax polio contains killed polio viruses and is administered intramuscularly or under the skin.